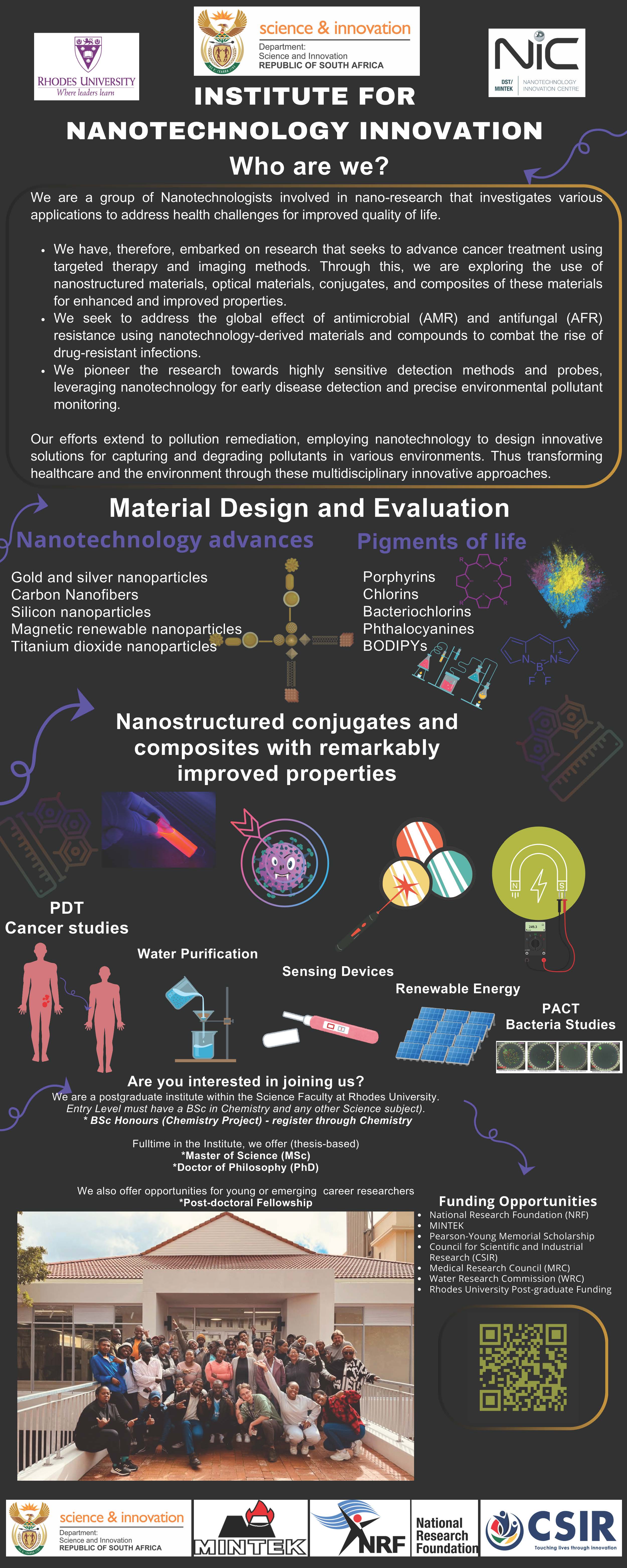

The formation of DSI/Mintek NIC is a Department of Science and Innovation (DSI) -initiated strategic partnering of research in academia and development in industry in order to bridge the innovation chasm between research and development. DSI tasked Mintek to identify areas of nanotechnology research in South Africa that have the potential to produce marketable nanotechnology devices. Mintek after consultation decided on Health as the theme.

Three centres were then established under Health: Sensors (Rhodes University), Bio-labelling (University of the Western Cape) and Water (University of Johannesburg). These centres will be national facilities and are expected to co- ordinate and promote nanotechnology in the health arena across South Africa. The Rhodes NIC – Sensor Division will focus on conducting fundamental and applied research towards using nanotechnology to design sensors for early detection of human diseases. The Rhodes University centre now houses major items of equipment previously in use by other institutions.