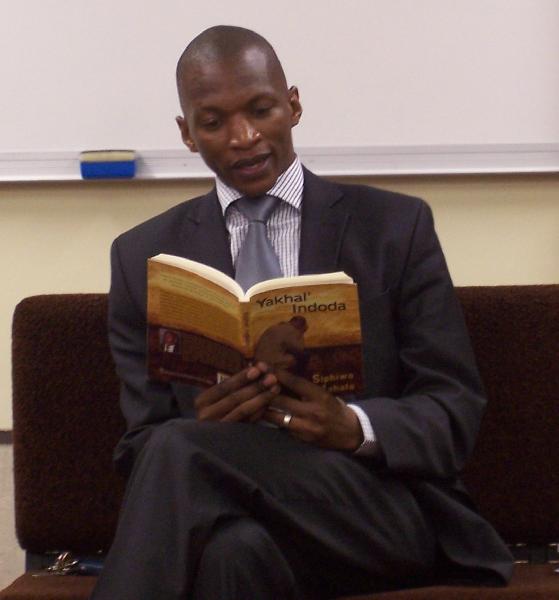

The English Department's Spring Seminar Series continued this week, when one of Grahamstown's own, Siphiwo Mahala, came home to present the isiXhosa translation of his novella “When a Man Cries” into “Yakhal'Indoda”.

“When a Man Cries” was originally written as a series of short stories. The fact that Mahala has himself been able to translate it into isiXhosa, and that a readership exists for it in that language, is very heartening for him; one of his goals at the Department of Arts and Culture (DAC) is to encourage people to not only write in their own languages, but to read in them.

Mahala was born and raised in Grahamstown, and is currently the Deputy Director of Books and Publishing with the DAC. After reading for his degree in Xhosa Literature at Fort Hare, he worked at the Grahamstown Schools Festival, and enrolled in a Creative Writing Course at Rhodes.

He recalled how he had been trying to write in his home language of isiXhosa, but had experienced so many obstacles that he began instead to produce his work in English. On being told that he was a “good storyteller” he decided to leave his job and pursue an MA in African Literature, to try to turn this gift into that of a writer.

The seminar was conducted as an informal interview, with Visiting Lecturer Lizzy Attree questioning Mahala on aspects of his work. Of particular interest was the tradition of masculinity and manhood carried throughout the book. Mahala explained that he was not sure that the decision to write about this was a conscious one.

As the only boy in his family, he was aware from a very young age of the imposed differences between himself and his sisters. He remembers seeing Bishop Tutu crying on television during the Truth and Reconciliation hearings as a defining moment, and asking himself if that made the Bishop less of a man. This led him to question stereotypical notions of masculinity.

Mahala says now, “You are not a man just because your foreskin has been removed. You are a man through the power of your actions.” And in his novella, his protagonist, Themba, abuses this power.

The book is also concerned with HIV, with the story ending on the ambivalent note of the audience, and Themba himself, not knowing his own status. Having begun to abuse his power, he molests the little girl who is in his care. Unable to face the reality of his guilt, he blames the women around him for tempting him.

Mahala explains how discouraged he became when various administrative troubles prevented the quick publication of the book into Xhosa. He could, he says, have written a book in English in the time it took for the translation to be published. But, he asked himself, what is the point of writing if the very people I am writing about cannot access my work?

To the great delight of the room, particularly the young members of Upstart, Mahala then read aloud for us in isiXhosa, marking the very first time that he had read publically from “Yakhal'Indoda”.