The media face multiple pressures both from within and outside the profession, writes Hopewell Radebe.

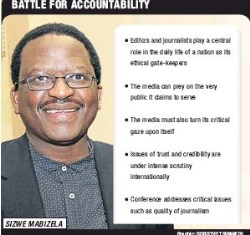

Journalists are facing the depressing reality of political instability, as well as a lack of transparency and accountability on the part of those entrusted by their electorate with political leadership, says Dr Sizwe Mabizela, deputy vice-chancellor at Rhodes University.

This explains how this year’s Highway Africa conference theme, Speaking truth to power? Media, politics and accountability, talks to the media community as the African continent celebrates 50 years of independence from “shackles of underdevelopment, colonialism and political subjugation”, Dr Mabizela says.

Over the years, the themes of this flagship conference of the university, have sought to address contemporary and critical issues of the day such as quality of journalism, the rise of citizen journalism, media and climate change and internet and democracy, he says.

The conference last week sought to encourage journalists to fearlessly tell “the story of rampant corruption, crass materialism and self-enrichment by the political elite and the politically connected”, berating across Africa.

Speaking in defence of journalism, director of BBC Global News, Peter Horrocks, says the critical role of the media on this continent is under threat from multiple pressures outside of journalism, as well as within the profession.

However, many remarkable individuals and organisations in Africa are practising great journalism under immensely difficult circumstances, he says.

What is encouraging is that debates on the ethics of journalism in Africa and about the role of international media on the continent are intense, and are contributing to improving journalism standards in general.

Mr Horrocks says an apt example is that while in 2007/8 the interests of some in Kenyan politics were served by inflaming public feeling, during elections this year some political interests were served by ensuring there was insufficient enquiry into past political misbehaviour. At the same time, the interests of some commercial international media were served by over-dramatising and caricaturing Africa.

All this is taking place amid

reverintimidation and rising threats of physical violence. More than 600 journalists have been killed in the past 10 years. In many cases, he says, they were not reporting from conflict zones, but rather on local stories in their home towns, revealing corruption and illegal activities.

“The increasing international policy focus, including in a recent United Nations Security Council debate, on the impunity enjoyed in much of the world by those who attack journalists is a development much to be welcomed.

“I call on all responsible media organisations here to support these efforts to combat impunity.” Mr Horrocks says it is ethical journalism that ensures scandals are not repeated.

“Ethics in journalism should not differ in UK or Africa or Asia. A set of values that shapes ethical journalism should be the same everywhere, and the cornerstone of those values is putting the public interest first. That is not the same as commercial interest or state interest,” he says.

The Panos Institute Southern Africa’s Vusumuzi Sifile says African countries should strive to build alternative media capacity within communities. Marginalised groups would then be able to engage and gain better access to information and knowledge.

“Alternative media have potential to amplify the voices of marginalised people to articulate development and livelihood issues affecting them. It also increases citizens’ demand for truth, accountability and transparency,” Mr Sifile says.

Rhodes University’s Prof Lorenzo Dalvit says mobile phones are increasingly becoming useful “watchdog” tools for ordinary people to keep government institutions accountable. For example, communities have used cell phones to record acts of police brutality, which has embarrassed the police service in SA, forcing senior officials to take corrective action. This is a trend world wide.

In many countries cell phones are being used as election monitoring tools to minimise fraud, while other applications have made it easier for remote communities to access essentials services, such as banking, information for agriculture, health and, lately, learning.

The University of Nairobi’s Jacinta Maweu warns that there are threats to media speaking the truth to the public they profess to represent and on whom their credibility relies. These include ethnic identity, which often creates tension in a journalist’s professional work This was witnessed in the media in Kenya when ethnic considerations and loyalties influenced the ethical decisions of journalists.

Often, too, subtle internal pressures are exerted to observe “silent policies” not to report negative issues that may endanger the business interests of “sister” companies, or might offend a big advertiser.

By: Hopewell Radebe

Article Source: Business Day