Writing: Reviews & Think Pieces

Of existential angst and F-bombs

Amidst the diversity of aesthetic, existential angst was apparently the collective narrative in this year’s Rhodes University Students Art Exhibition in the Fine Art Department during the just ended annual National Arts Festival in Grahamstown.

The artworks were overtly emotive, shrewd and instinctual and yet somehow gave the impression that they were connected to the personalities of their creators, who grapple with coming of age – how to find meaning in a fast paced, constantly changing world. Academics, dating, an overheating planet, uncertain economy, a blurry political future are all issues can cause extreme anxiety, despair or hopelessness.

Grappling with thoughts around the purpose of life can be just as frustrating as finding meaning in the purpose of art today. It is expected for art, at an academic level, to be grounded in some form of ‘critical theory’ by taking scholarly approaches that seek to challenge socio-political, historical and ideological issues. The most popular issues broached today is art being the multiplicities of feminism, decoloniality, geopolitics, race, gender and queer theory - the list is endless.

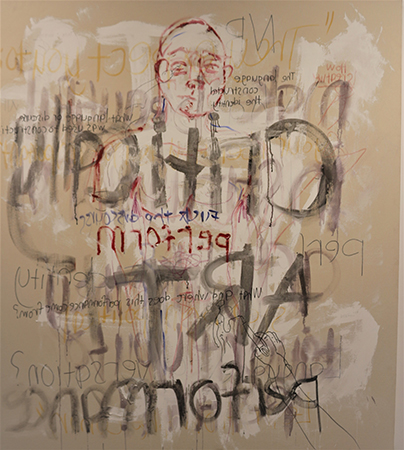

It is therefore no wonder the F-bomb – used here as a euphemism for the word “fuck” – was frequently dropped throughout the exhibition. From exclamations such as “What the Fuck?” and “Freaking the Fuck out!” in Joshua Paper’s (2nd year) digital prints entitled The Gradual Increase, to Endometri – Oh My Fucking Gosh, Someone Please Kill Me by Nokulunga Ncongwane (2nd year). Carol Nelson’s (4th Year) painting entitled Critical Art which imperceptibly has the words “Fuck the discourse” horizontally flipped and reading back to front in it, as well as several “Fuck Me’s” in a digital video entitled They’ve Got To Eat by Aaron Robert Adriaan, Daniela Honey, Emma-May Kane and Emily Webster (1st year).

The F-bomb is vulgar slang, whose literal meaning refers to the act of sexual intercourse but is commonly used in various situations to express annoyance, contempt, impatience, disapproval or angst – in this case existential angst. Such is the context in which the word was used in the works featured in this exhibition. One might suggest that in recent times the F-bomb has lost its invective potency as an offensive word in popular culture due to its regularity, particularly in Hollywood cinema and hip-hop music, both of which are popular sources of entertainment among students. In the exhibition the slur streak proceeded beyond the F-bomb with “U Kunt” in Die Alphabet a digital print of an idiosyncratic alphabet created by Tasmin Randall (2nd year), an exclamation that may need no explanation.

Nevertheless, the impression of soul searching continued through the exhibition with Awkward Me by Bethany Meyer (2nd year), on the face of it, a self-portrait that speaks to the evaluation of the self.

Juilia Arbuckle’s (2nd year) video animation Milennihilism perhaps encapsulates the suggested premise of existential angst the strongest. Arbuckle’s ‘milennihilism’ is a self-made compound word combining ‘millennial’ and ‘nihilism’, the former being a generational demographic of youths born between 1995 and 2010, while the latter is synonymous with pessimism, skepticism or emptiness. In the video, a Pumpkin-Spice-Soya-LattewithCoconutMilk-drinking millennial who is also a vegetarian that thinks avocado toast is “bae” and “Netflix is life” is confronted with the thought that life is pointless and at the end of the video asks “Is this all there is?”. In the end she exclaims “Hello darkness my old friend!” as she drifts off into the darkness of outer space, and the looped video starts again with a tombstone that reads “Here Lies A Millennial”.

The soul searching continued in the work of Viwe Madinda’s (3rd year) installation entitled Andikanya Ndigalelekile which may be translated as “I’m here, deal with me”. Appropriating the mysterious, the hidden and the spiritual, she claims her cultural identity and brandishes it in a white-cube gallery declaring her subjectivity in a highly westernized society and plays on underscoring the tensions therein. It can be read as the work of a young African artist announcing that at the end of such a search she knows who she is and should be accepted the way she is in terms of gender, culture, ethnicity and all. The work featured a cluster of figures performing a ritual; it comprised three mannequins draped in red cloaks with their faces covered, the central figure held a bowl containing imphepho (African Sage), an entry-level medicinal herb used by izangoma. The two flanking figures both held whips in one hand, a wooden pole with animal horns atop of it with unlit candles on the floor surrounding them. Four photographs in which she simulates a ritual were also on display. Because of its mystique, the work was among the most photographed in the exhibition.

Another work that was among the most photographed was Mi nouan Type 1, a large semi-abstract oil painting by Akissi Beaukman (4th year). As part of a set of three, it had the relatable face of an expressionless woman whose eyes, hair and neck were covered in multicolored doodles of glittering paint.

The search for self as a theme, embroidered in the notion of walking, continued in the work of N’lamwai Chithamo (3rd year) in a print and digital video entitled Milieu Panorama. It features an elaborately illustrated young man walking through woods coming across the occasional house, streams and bridges; it was accompanied by the sound of footsteps stepping on dried leaves.

In Lungisa Madywabe’s (1st year) The Ambiguity of the Emoji, a set of four digital prints questioned the honesty of the emoji or its sender. The ideograms that have become synonymous with communicating emotions through electronic messages and social media may not always reflect the true sentiments of its sender, on one of the prints is written: “I hate this emoji, Are you happy. Is it secretly mad? Unhappy. Does it want to kill you? Is it fed up? You will never know”.

Trolololo, a painstakingly crafted metal sculpture by Taryn Jade Benadé (1st year), derives its name from the laughter of an internet troll. The act of trolling is deliberately making random, unwelcome and often insulting comments on social media threads. Often delivered by individuals using fake accounts, trolling is tantamount to online bullying and can cause angst on someone who posted a harmless comment or status online. “Trolololo” is sometimes used casually as a playful gesture among friends who deliberately troll each other. Benadé’s sculpture features a severed hand, perhaps indicating that someone has cut off the hand of an irritating internet troll.

A series of ten photographic prints by Aaron Robert Adriaan (1st year) featured enlarged head and shoulder portraits celebrating the diversity of race and by extension ethnicity. All the subjects in the photos were bordered off by a thick red margin that also ran across their faces with the words “This means nothing”, which lends the title to the work.

Look beneath the Surface by Maeve Fagan (3rd year) and Untitled Lands 1-5 by Justin Share (4th year) were clusters of photographs that respectively lent the ongoing South African land debate to mind. Fagan’s photographs are of what appears to be four photographs a farm house shimmering in the reflection of a stream whereas Share’s featured five black and white images of a bushy outcrop with various subject matter, all of which were painted over with a large single brushstroke of blood red oil paint. It is as if Fagan’s work invites the viewer to look ponder deeper on the land issue, while Share’s work although calm with its open landscapes, it is also violent with the color of the paint and the manner of the brush stroke it evokes the blood that has been spilled and continues to be spilled over the land.

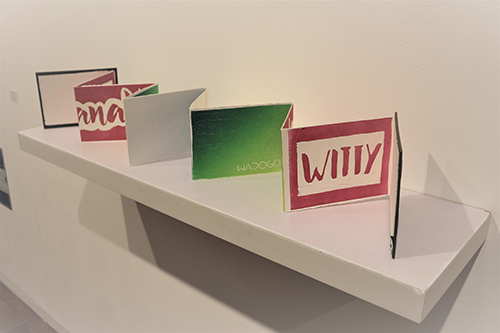

In contrast, Serendipity by Aadila Chand provides for a more pacifying viewing experience. Although the original comprises four acrylic and resin on canvas works, they were exhibited as a group of photographs. In Wynona Mutisi’s (2nd year) witty Wild, Wise Wynona exemplifies a diversity in the use of classical Fine Art materials relief print on fabriano and book binding material.

Also on display were a group of ceramic heads from the 1st year sculpture class by Keiryn O’Connor, Fatsani Mndolo, Bandzile Hlatjwako, Luntu Jonginamba and Liam Ogle respectively.

The student exhibition is an annual selection of artworks produced by undergraduate students from first to fourth year during the first semester. Selected from a wide range of media, they convey diverse approaches to project briefs and selected self-directed study. Being and small physically isolated from the gallery circuits of major South African metropoles, exhibiting during the NAF provides the students with a considerable amount of exposure. This year on average, the exhibition received an estimated 4,000+ visitors during a course of 10 days.

~ ENDS ~

1st year sculpture class - Keiryn O’Connor, Fatsani Mndolo, Bandzile Hlatjwako, Luntu Jonginamba and Liam Ogle respectively.

Akissi Beaukman, Mi nouan Type 1, 2018, oil on canvas

Carol Nelson, Critical Art 2018, oil on canvas

,_2018,_digital_print.jpg)

Joshua Paper, The Gradual Increase (detail), 2018, digital print

Juilia Arbuckle, Milennihilism, 2018, video animation

Nokulunga Ncongwane, Endometri – Oh My Fucking Gosh, Someone Please Kill Me, 2018, mixed media

Rhodes University Students Art Exhibition 2018

Taryn Jade Benadé, Trolololo, 2018, metal

Viwe Madinda, Sibathathu, 2018 colour photographs

Wynona Mutisi, Wild, Wise Wynona, 2018, relief print on fabriano and book binding material

Andrew Mulenga is a PhD candidate with the NRF/DST SARChI Chair Geopolitics and the Arts of Africa, Arts of Africa and Global Souths research programme headed by Prof Ruth Simbao at the Department of Fine Arts, Rhodes University, South Africa

Last Modified: Mon, 11 Feb 2019 10:44:15 SAST