Writing: Reviews & Think Pieces

Pemba’s prodigal sons: Exegeses of forgiveness

The University of Fort Hare Collection’s (UFH) recent showing of 24 rarely exhibited artworks provided for stimulating viewing of works by black South African masters, who lived and worked during the apartheid era at the Ann Bryant Gallery in East London, South Africa.

These paintings piqued renewed interest, and not only because these were merely a fraction of about 2,500 in the university’s collection, rather by providing for general fascination to a new generation of viewers. These paintings created intellectual appeal that confirms the rich and often overlooked heritage of painting by black artists in the Eastern Cape.

Nevertheless, as much as the collection is linked to the history of life lived during the liberation struggle and is loosely described as historical or social commentary, some of the themes in the paintings spoke to more universal subjects, such as forgiveness. Two of such works are paintings by George Pemba (b.1912- d. 2001).

Owing to their titles, Pemba’s works The Return of the Prodigal son (1960) and The Prodigal Son (1971) – which, according to UFH Vice-Chancellor Sakhela Buhlungu, were being publicly exhibited for the first time – may be implied as exegeses of one of those most popular of all Jesus’ parables in the Gospel according to Luke (15: 11-32).

In the allegory, a son requests for his inheritance and leaves his parents’ home, only to hurriedly squander it on an excessively extravagant lifestyle – in fact the term “prodigal” itself literally translates to “a person who leaves home and lives a wasteful and extravagant life but returns repentant”. Likewise, in the biblical account, arriving sick and impoverished, the protagonist returns home where his father, overpowered by tears as he welcomes and forgives his son, warmly receives him. This figuratively – and in a theological context – suggests God forgives all those who repent.

In Pemba’s paintings, the allegory transcends any literal Biblical references. As much as the works do evoke the idea of repentance, the triumph of love, kindness, tolerance and compassion, the images specifically suggest forgiveness within familial ideology. One senses that his portrayals have a personal touch to them, not only to the artist’s own life but also to any viewer who has experienced similar encounters of forgiving or being forgiven in a family context.

A brief survey of critical biographies on Pemba (see Huddleston 1996; Feinberg, 2000; Nolte 1996) suggest he was an ardent family man and was immersed at an early age into providing for not only his own nuclear family but for the children of deceased siblings. He was also very attached to his widowed mother who lived until an advanced age. Before his death, Pemba’s father is said to have been very supportive of his son’s art, as he found him his first buyers. This is years after an incident where as an adolescent, Pemba ran away from home for fear of being physically punished by his father after he had abandoned the family heard of cattle in order to go and watch the bioscope. His father went looking for his lost son and only found him about a week later in another town. Pemba’s biographers mutually imply that this was what would inspire him to return to the theme of the lost son – the prodigal son—as an artist consecutively throughout his long career, with the first of such a work being one that he did in 1945.

However, one might suggest that it is not this one incident that inspired the theme in his work over the years. Being committed to a large family in which he inadvertently assumed the role of patriarch himself, he may have forgiven and been forgiven repeatedly in his lifetime. As it happens, both he and his older brother struggled with alcoholism, and in one account Pemba admits that it almost ruined his life and marriage, that it affected his health, work and the relationship he had with his family members. Fortunately, he would triumph over alcoholism and subsequently gain forgiveness for it.

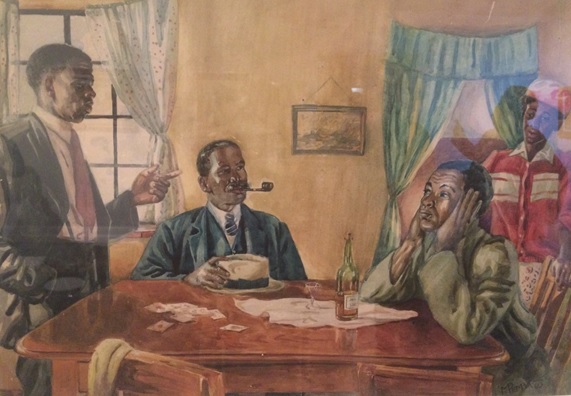

Fig. 1. George Pemba The Return of The Prodigal Son, 1960, 32 x 47 cm, water colour. The University of Fort Hare Collection. (Photo by Andrew M. Mulenga, 24/05/2018, Ann Bryant Art Gallery, East London)

Nevertheless, in the 1960 version entitled Return of the Prodigal Son (Fig. 1), the eponymous character appears subservient, seated at a table with both hands to the sides of his head, considerately facing one of two patriarchal figures standing across from him. The standing man has his finger pointed towards the prodigal son as if castigating him, reminding him of his wrong doings. This figure could be the father, or an uncle - it is hard to discern his familial role in the picture in relation to the second patriarchal figure who is also seated at the table. The seated man who appears the same age as the standing figure, except for the subtle highlights of grey hair on his moustache and hair, has a more sympathetic expression on his face. He too might be an elderly uncle who has come to witness the episode; his smoking pipe and trilby suggest he is in transit or has just been invited. Behind the prodigal son is what appears to be a mother figure, affectionately holding on to the back of his chair as she looks at him with a kindhearted expression. She is fashionably dressed in a red cardigan, pink barrette and floral dress. Similarly, the two men are smartly dressed in suits as was the custom those days, when men who worked mostly in factories and mines would wear a suit to church, funerals, weddings or at the shebeens on pay day. This sense of fashion was heavily influenced by the jazz and blues stars of the day in places such as Sophia town or Kofifi, as the style of dress can also be referred to. The furniture depicted and the manner in which the characters are dressed suggest a family that is living relative prosperity for a black family of the time – this lost son has surely not returned to an underprivileged home.

The protagonist in comparison is shabbily dressed on his return to the comforts of home. Set before him is half a bottle of what appears to be sherry, owing to its colour and the glass that accompanies the drink. Although the refreshment is set before him, he does not seem interested in it at the moment but may be more concerned with being welcomed back home and forgiven; he is in the process of being reprimanded before he is forgiven by these two patriarchal figures.

Commenting on the 1945 iteration of the prodigal son – which has a similar portrayal of unyielding authority -- in a catalogue essay by Art Historian Jacqueline Nolte, she proposes:

“This episode is important not only for what it says with regard to learning the extent of patriarchal power and protection, but also for its indication of broader patterns of liberating and repressive power. The episode raises questions about the formation of human will and desire, and about how ‘dominative’ power ‘allows’ the promotion of subjectivity and physical coercion gives way to habitual consent” (Nolte 1996: 39)

Fig. 2. George Pemba The Prodigal Son, 1971, 62 x 49 cm, oil on board. The University of Fort Hare Collection. (Photo by Andrew M. Mulenga 24/05/2018, Ann Bryant Art Gallery, East London)

In constrast, in the 1971 iteration of The Prodigal Son (Fig. 2), the disposition of the patriarchal figure appears softer. As opposed to the seemingly unyielding depictions of father figures in the earlier portrayals, in this one his father has his arms affectionately stretched towards the returning son whom he is visibly pleased to welcome home. Dressed like a wanderer, the son’s gestures are supplicatory, his positioning is that of knees in the process of buckling as he looks up to his father with a mixture of hopefulness and hopelessness, his facial expression ostensibly on the brink of tears. The dramatization in this episode is uncompromisingly theatrical. Centre stage, is a hospitable matriarchal figure, her hands gently raised to her chin in a gesture of disbelief towards the return of her son. Her face is filled with remarkable restraint as if waiting for the incidence between father and son to quickly pass by, with the patriarch having the first word and formally forgiving the son, perhaps by means of a hug and a few words of clemency. She is conceivably an incarnation of the artists own mother, dressed in a red blouse with a frilly white collar and white headscarf. This is a popular uniform among Christian women’s groups, an outfit in which Pemba depicts his mother in the autobiographical painting of his father Titus’ funeral entitled Funeral Procession (1930).

The mother is flanked by two other children; to the left, an elegantly dressed young lady, her hands placed in front and modestly held together by thumb and finger as she politely watches the episode unfolding in front of her. Her head tilted to one side with suppressed emotions, she too awaits for the pardon formalities to conclude so that she can welcome her returning sibling. To the mother’s right, is a smartly dressed young man, most probably the lost son’s brother. His face is not as welcoming as the rest of the family, he looks at the returning sibling disapprovingly from the corner of his eyes, possibly unable to put his disapproval into action in due respect to the patriarch who is wholeheartedly welcoming the lost son home.

In the biblical account, this mistrustful sibling represents the older of two brothers, the one who loyally remained at home in favor of his father, working the fields and obediently waiting for the right time to claim his inheritance. According to the parable, this son was in the field when the father had already welcomed his brother home, dressed him in the best robe, put a ring on his finger, sandals on his feet and had the servants kill a fattened calf for a welcome feast. Angrily, the older brother refused to join the feast and reproached his father, pointing out he was the most loyal of the sons and not even a goat had ever been killed in his honour, to which the father responds:

‘My son,’ the father said, ‘you are always with me, and everything I have is yours. But we had to celebrate and be glad, because this brother of yours was dead and is alive again; he was lost and is found’ (Luke 15:31)

Without unduly implying a recital of moral rectitude here, it is in fact this brother on whom the lesson of forgiveness and compassion is hinged. He is a reminder of how difficult forgiveness can be to bid, especially when in one’s own opinion the person seeking forgiveness may be deserving of a punishment.

In conclusion, in the lower part of the composition is a dog, and the fact that it is inside the house implies that it is well cared for, figuratively , one might ask, if the dog is welcome in the house, what of a long lost son? The dog is also of symbolic significance as it is often placed as a sign of loyalty in art. The dog too appears to be hesitantly sniffing at the lost son, trying to catch a familiar scent under the grime he might be covered with, returning as beggar who had been sleeping outdoors. The door behind him symbolizes a passage, open to forgiveness that can be walked through if willing to swallow one’s pride and accept one’s mistakes. At the top most position of the composition is a lamp, a symbol of hope, suggesting that there is hope in forgiveness. Return of the Prodigal Son and Prodigal Son provide for a reading of two sides of forgiveness, one with unyielding prerequisites and the other with unconditional kindness.

Short Biograph

Born George Milwa Mynaluza Pemba at Hill's Kraal, Korsten, in Port Elizabeth on 2 April 1912, his life covers nearly a century. The fifth child of Rebecca and Titus Pemba, a self-disciplined couple who adhered to the Christian faith. He witnessed the struggle to create a democratic South Africa and lived to see the overthrowing of apartheid, which took root when he was only two years old as the Natives Land Act became law in 1913. He was only 11 years old when the Urban Areas Act which only allowed black people to live in the city if they were working for a white person. Struggling against such unjust laws would afford Pemba the position to record such trials and tribulations through his painting.

While Pemba’s achievements as an artist will only be fully appreciated in his later life, he was not new to accolades, as a child he won the Grey Scholarship to attend Paterson Secondary School. Encouraged by his father he began producing portraits from photographs of his father's employers. His father was killed in a motorcycle accident in 1926. His work was first exhibited at the Feather Market Hall in Port Elizabeth in 1928, when he was sixteen.

In 1931 he obtained a Teacher's Diploma at the Lovedale Training College in the Eastern Cape. This is the same year that he was only one of two South African artists whose works were accepted for the “Negro and Bantu” exhibition in Port Elizabeth, as well as a second exhibition in Grahamstown where he won both first and second prizes. At Lovedale, Pemba produced illustrations for books published by the Lovedale Press. He continued to work there until 1936 until he took up a teaching post at the Wesleyan Mission School in King William's Town. In 1934, Pemba was treated for a burst appendix and he spent his hospital stay drawing pictures of nurses and doctors, and these caught the attention of landscape painter Ethel Smythe who took an interest in Pemba and offered him tutelage.

In 1936, he studied under Professor Austin Winter Moore for five months at Rhodes University, which was made possible through a bursary awarded from the Bantu Welfare Trust. During this period, his work was included in several exhibitions including the May Esther Bedford competition in fort hare described as “the first exhibition for blacks”. He won first prize where George Sekoto, who would later become more famous, took second prize. Pemba was awarded a second bursary in 1941, where this time he spent two weeks at Maurice van Essche's studio in Cape Town attending art classes.

Pemba neither sought nor anticipated wealth but only wanted his work to be recognized, and in 1979 the University Of Fort Hare awarded him an honorary Master’s Degree in Fine Art. In 1992, an exhibition served to commemorate his 80th birthday was hosted at the King George VI Art Gallery in Port Elizabeth, which he also attended. He died in 2001 outliving the majority of his, perhaps more famous, contemporaries, and having remained in South Africa and not gone into exile, he left a priceless legacy of works and surely deserves to be mentioned in the pantheon modern and contemporary African art. His work can be viewed at The De Beers Centenary Art Gallery at the University of Fort Hare in Alice, as well as at the Nelson Mandela Metropolitan Art Museum.

~ ENDS ~

References:

Feinberg, B. and Proud, H. 1996. (Eds.), George Milwa Mnyaluza Pemba, Retrospective Exhibition, South African National Gallery 1996

Feinberg, B. 2000. George Pemba, Painter of the People, Viva Books, Kensington, 2001, South Africa.

Holy Bible, New International Version, 2011, Biblica, Inc.

Huddleston, S. 1996. Against All Odds, Jonathan Ball Publishers (Pty) Limited, Jeppestown, 2043, South Africa

Acknowledgements:

Ann Bryant Art Gallery, East London

The University of Fort Hare Collection

ARTS OF AFRICA AND GLOBAL SOUTHS research programme

Andrew Mulenga is a PhD candidate with the NRF/DST SARChI Chair Geopolitics and the Arts of Africa, Arts of Africa and Global Souths research programme headed by Prof Ruth Simbao at the Department of Fine Arts, Rhodes University, South Africa

Last Modified: Mon, 11 Feb 2019 10:36:24 SAST