By Sam van Heerden

Fighting climate change is high on the world’s agenda, and many believe planting trees is a powerful way to fix the crisis. Forests can capture and store carbon dioxide (CO2), the main culprit behind our warming atmosphere. But Associate Professor Susi Vetter, from the Rhodes University Botany Department, argues that the drive to reforest the earth can be misleading and, at worst, harmful to people and the planet.

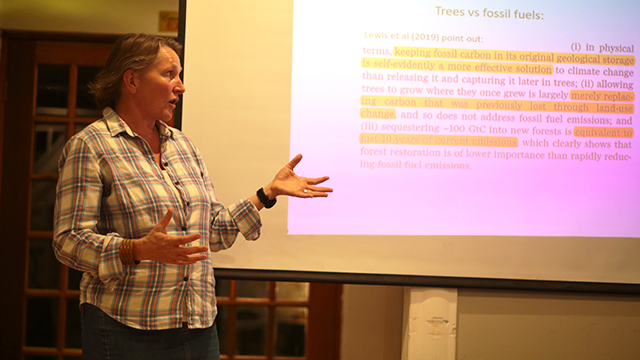

“People have been talking about planting trees to save us from the climate crisis for quite a long time. But for the last few years, the targets for reforestation have been staggering,” explained Prof Vetter, who was speaking at an event hosted by the Wildlife and Environment Society of South Africa (WESSA) last week.

Global initiatives, such as the United Nation’s Bonn Challenge, create reforestation targets and encourage governments and companies to pledge their commitments. A publication in 2019 estimated that through reforestation, we could gain an extra billion hectares of trees, which is roughly the size of the United States. This would allegedly capture about two-thirds of man-made carbon emissions.

But Prof Vetter and many other scientists are sceptical of these large numbers. While the average amount of deforestation occurring every year has been relatively stable, CO2 emissions continue to rise. Restoring degraded or deforested areas can only capture what has been lost to deforestation alone. “A recent paper estimates that at best, this only amounts to about ten years of emissions. It’s a short-term measure and it won’t stop the crisis,” Prof Vetter said.

A significant number of environmentalists agree that preventing fossil fuels from being taken out of the ground in the first place makes more sense. But what dominates much of the conversation around climate change mitigation is a significant push towards ‘carbon offsets’: capturing or limiting CO2 to compensate for already-released emissions. “Many companies and other parties have a vested interest in offsetting carbon emissions because emitting carbon is what makes them money,” said Prof Vetter.

Although the image of someone planting trees to save the planet has become a staple in the media and many organisations, the reality is that reforestation raises a host of environmental and political challenges.

For one, numerous areas across the globe marked as reforestation-friendly are savannahs and grasslands in the Global South. This includes our own Kruger National Park and the Brazilian Cerrado savannah, the world’s most biodiverse grassland. These biomes are home to rich wildlife and also form an essential part of people’s way of life – central to providing food, livestock farming, water, and cultural practices.

These grassy regions are seen as deforested or degraded. Yet, Prof Vetter disagrees: “We know that our grasslands and savannahs are open and grassy because of fire, grazing, and a long evolution of ecological processes. And they provide critical ecosystem services. But they are being presented to governments as opportunities for planting trees.”

Ironically, these grasslands also play a significant role in regulating our atmosphere. They store a third of the world’s carbon, which is generally ignored in carbon capture calculations. Since the soil holds much of this carbon, it is also more secure than carbon stored in forests, which are vulnerable to fire, insects, drought, and the resulting release of CO2. And climate change is already making these threats worse.

Prof Vetter explained that our obsession with trees, and the idea that they are always good, is a colonial legacy The French, and later the English, were worried about desertification and drought in their colonial territories.

“The general assumption was that areas which are dry and look degraded to European sensibilities were once forests and that humans destroyed them. If you could bring back the forest, then the rain and fertility would follow,” said Prof Vetter. “There was this genuine belief that there needed to be a certain amount of tree or forest cover for the climate to be suitable for ‘civilised’ habitation.”

But in reality, reforestation can often do more harm than good. Numerous initiatives emphasise the need to plant indigenous trees, but these are not fast-growing enough to meet the incredibly ambitious targets. Large-scale plantations of fast-growing species not only allow large targets to be met quickly, they also generate revenue. It therefore doesn’t come as a surprise that many areas pledged for restoration are destined for large-scale plantations of harmful alien species such as pines and eucalyptus for timber and pulp, and agricultural crops like oil palm.

Funding for these projects often comes from companies that can profit from planting commercial trees or selling carbon offsets. And while private and government actors benefit through making a profit while appearing environmentally responsible, the local populations often suffer.

“These projects have a track record of excluding existing land users. And even if clothed in participation, the interventions tend to be top-down,” Prof Vetter explained. “On the whole, marginalised populations [who contributed the least to climate change] are bearing the costs of this kind of climate change mitigation.”

“Restoring and planting forests is promoted as a win-win-win solution for climate, ecosystems, and people, without acknowledging the inevitable trade-offs,” explained Prof Vetter. She reiterated that it is crucial to distinguish afforestation – planting trees where they didn’t historically occur – from forest restoration – bringing back forest where it once occurred. Forest restoration does benefit ecology, people, and the climate, but it needs to be the “right tree, in the right place”.