By: Aretha Phiri

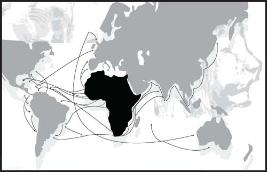

Celebrated Ghanaian writer and academic Ama Ata Aidoo has no time for “Afropolitans”. This is a notion popularised by the self-described “multi-local” author Taiye Selasi. Afropolitans are a current, cosmopolitan generation of “Africans of the world”.

But Aidoo believes that Afropolitanism is “evidence of self-hatred”. Its proponents, she charges, use it as a “fancy moniker” that tries “to mask the terror associated with Africa”.

Her objections speak to widespread, global calls for the decolonisation of institutionalised cultures. This is of particular interest to university communities at large right now. In South Africa, one crucial and complex aspect of this process is a call to Africanise university curricula. This is certainly necessary. But, as ongoing debates around African literature reveal, it must be done cautiously.

One element of this “Africanisation” debate involes assessing the value of contemporary literature written by Africans who live in the diaspora. Its critics complain that current Afrodiasporic literature is not in tune with everyday life on the continent. They see its versions of Africa as sanitised and Westernised.

I disagree. These works take students beyond their national and personal borders. This is crucial in these times of global cultural flux.

Beyond national and personal borders

The notion that contemporary Afrodiasporic fiction is socially and culturally inapplicable is typically couched in racialised and nativist interpretations about what is or who isn’t African. This highlights the ideologically safe and unimaginative spaces that many still occupy. It also reveals something about how deeply ingrained colonising structures are.

The question of who writes, and what is written, about Africa is both pre- and over-determined. The emphasis on ethnic and cultural distinctiveness risks reestablishing exclusionary inter- and intra-racial hierarchies.

Contemporary black African writers in the diaspora are contesting precisely this imposition of culturally representative literature. Some examples include Maaza Mengiste’s cynical article “What makes a ‘real African’?” and Binyavanga Wainaina’s sarcastic instructions on “How to write about Africa”. Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s novel, “Americanah”, is a fictive caution about an issue she first raised in her 2009 TED Talk, “The Danger of a Single Story”.

As novels such as Selasi’s “Ghana Must Go” reveal, contemporary Afrodiasporic writing expresses less explicitly politicised, ambiguous versions and visions of Africa and the African diaspora. In doing so, it transgresses what Helon Habila describes as “pass-laws” that seek to restrict where “African literature can go”.

No need to reinvent the wheel

Rhodes University in Grahamstown, South Africa, recently organised a conference at which concerned scholars gathered to reexamine established ideas about African literature and philosophy.

We weren’t trying to reinvent the wheel. This issue is not new, after all. The first African Writers’ Conference was held at Uganda’s Makerere University in 1962. There, scholars debated the significance and place of African literature written in English for nation states on the cusp of independence. More than five decades on, the conference offers valuable lessons to universities trying to critically reconceptualise educational curricula for post-colonial subjects.

But the wheel must be modified. It needs to reflect and engage South Africa’s own post-traumatic, post-apartheid landscape. In this respect, two recurring challenges emerge: first, what exactly is (black) Africa(n) in this fragile, shifting global village? Second, how does a university “Africanise” its curricula in the face of different ideologies and realities?

Global cultural flux

I teach contemporary Afrodiasporic literature to undergraduate students. In my experience, these works speak to their encounters with subjectivities beyond their national and personal borders. We exist in a time of profound global cultural flux. Against this backdrop, inflexible and insular readings of both Africa and Africans do not adequately interpret the diversity and complexity of their own subjective realities.

Contemporary Afrodiasporic literature’s worldly reinterpretation of Africa and Africans presents imaginatively inclusive visions. In its responsiveness to ever-shifting contexts and realities, it is committed to revealing what author Ben Okri calls the “strange corners of what it means to be human”.

Universities envisaging getting closer to what writer Ng?g? wa Thiong'o called “decolonising the mind” could stand to take current Afrodiasporic literature seriously. These works can help in the push to realise genuinely transformed, revitalised and reflective, alternative narratives of Africa.