There has been a resurgence of interest in the potential for state-led development, not least because of the failures of purely market-driven developmental measures to deliver widespread gains in health, education, environmental sustainability, employment, crime reduction and other essential anchors of lasting development. Spectacular developmental achievements in East-Asian contexts have shown what state-driven development can achieve, but their successes have often come at the cost of democratic accountability. It is also unclear how applicable the model is outside of Asia.

One of the most challenging developmental questions therefore remains coming up with conceptually neat and practically workable models in which socio-economic and political forms of institution-building come together, both to explain the developmental realities of contemporary societies and to suggest ways of lastingly improving them.

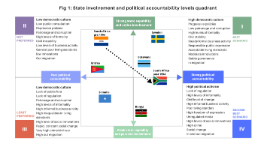

What might this look like in an African context? Development from local to national levels is driven mainly by two variables: first, the relative strength or weakness of state and government involvement in the management of public affairs and resources, and second, the possibilities for ensuring political accountability.

When combined, this leaves us with four basic pathways towards development. By looking at each of these and the institutional conditions frequently accompanying them we can get a snapshot of the opportunities or challenges that have promoted or collapsed the sustainable economic development of many post-colonial African countries.

Figure 1: State involvement and political accountability levels quadrant

When looking at the figure, in which each quadrant represents one of the four typical developmental scenarios, some complexities need to be taken into account. While some countries present themselves as the best prototypes to be located in one of the four quadrants at one point in time, many countries exhibit a mixture of these characteristics and straddle more than one quadrant. The rate at which a country can stay in one quadrant is also different and dependent on its own internal socio-economic dynamics as well as other global forces out of its control. In some countries, sudden changes, for example in political leadership, can set countries onto completely new trajectories. In other cases, a lack of state capacity in dealing with things like sudden natural disasters could also spell the beginning of a new direction in a country’s development.

Nevertheless, what is important for human and economic development within any country are the capabilities and levels of involvement of the state and government in sound and rational planning and execution of strategies. No less essential is the extent to which citizens can hold politicians and state officials accountable for the soundness and implementation of official developmental plans.

In the illustration, African countries that are experiencing full-on civil wars, such as Somalia in the last decade, can be located in the least preferred Quadrant III.

Eritrea, while characterised by a strong and involved state that promotes a political environment that does not encourage citizen free expression, for example through draconian laws that limit media freedoms to hold politicians and officials accountable, presents a prototypical case of the least desired state of development in Quadrant II. This state is characterised by low social innovation, generally poor living standards and high levels of outmigration, which have been observed in at least the last two decades.

A number of African countries that are not at war and are currently presented as the most functional cases, with vibrant economies, innovative informal sectors and double-digit levels of GDP growth, can be located in Quadrant IV. One of the best examples of this is Kenya. While there is a healthy level of public media activity, and high levels of social and technological innovation, a high proportion of the country’s employment is in the informal sector. In addition, there are endless reports of state and government patronage and corruption.

Very few, if any, countries in Africa can be located in Quadrant I. Botswana is, perhaps, one of the few countries on the continent that comes close to this characterisation, with a relatively capable state in formulating and implementing social policies within a relatively liberal and democratic political atmosphere.

South Africa, on the other hand, is currently characterised by strong media freedoms and democratic political expressions and has robust constitutional platforms to hold its government and state officials accountable on varied service delivery issues. However, the South African government has been less capable in formulating cohesive and effective long-term socio-economic policies, while the state is increasingly being challenged at implementing many government policies, including the challenges of protecting or promoting constitutional rights. With less effective government policy-making and increasing failures of the state in implementation of policies, it is no surprise that the country is currently characterised by a growing level of informality in different spheres of social life, including growing informal employment, alongside increasing crime levels that would locate the country mostly in Quadrant IV.

In historical terms, South Africa has nevertheless improved its locational position post 1994, with growth and public spending being far more equitably spread than they were under apartheid. South Africa has therefore migrated from a clear location in Quadrant II to attributes that would locate it mostly in Quadrant IV in the current political dispensation.

But there is no cause for complacency. The trend indicates that with gradual erosion of government and state capabilities the country is at growing risk of becoming one of the prototypical cases of African countries that can be squarely located in Quadrant IV.

It is apparent that to get the country to the most desired location of Quadrant I much focus needs to go into the way government is reconfigured for improved functionality. This entails improving the relationship between government and the state for purposes of building resources and capabilities at both technical and human levels. Efforts need to go into how current and new legislation is used to ensure that government is configured in a way that promotes the formulation of policies that serve to realise and protect our constitutional goals. New policy decisions also need to address how the weakening capacity of the state is rebuilt.

When thinking about the complex web of developmental challenges in South Africa and other African countries, the schema developed here provides a simplified tool for understanding complex socio-political and economic dynamics at play in specified periods and the possible paths taken to get there where data is available. Aside from its conceptual value, this schema also provides the basis for long-term economic and social policy interventions by stakeholders that can be fit for context, and that can begin to address the developmental challenges of African localities starting out from where they are at politically.

Source: Prof CN Mbatha, Rhodes Institute of Social and Economic Research (ISER) and Prof NN Mkhize, Nelson Mandela University (2020)Please help us to raise funds so that we can give all our students a chance to access online teaching and learning. Covid-19 has disrupted our students' education. Don't let the digital divide put their future at risk. Visit www.ru.ac.za/rucoronavirusgateway to donate