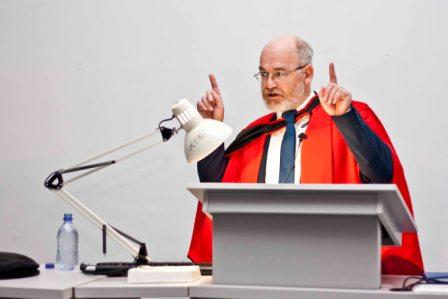

“Is that Dan Wylie in a tie?” a disbelieving voice whispered in the packed lecture theatre. “Goodness, now we really know this is a special occasion.” As indeed it was, an Inaugural Lecture given by one of South Africa's renowned literary talents who is fast becoming acknowledged as a pre-eminent conservationist and a proponent of the style of literary critique known as eco-criticism.

Professor Wylie is a writer, a poet, and a lecturer in the Rhodes University English Department. In the year 2000 he published a revised version of his PhD work, entitled 'Savage Delight – White Myths of Shaka.' In 2008 he was the recipient of the Vice-Chancellor's Book Award with his follow-up biography of the legendary Zulu chief, ‘Myth of Iron’. He is a past winner of the Ingrid Jonker and Olive Schreiner book awards and the Rhodes University Environmental Award. His most recent publication is entitled, simply, 'Elephant', and these majestic land animals played a major role in his lecture, entitled 'Elephants, Compassion and the Largesse of Literature'.

Why is a literary professor writing about elephants? Well, says Prof Wylie, it is because he discovered that he could combine his love of literature with his passion for natural history in the practice of eco-criticism, a field in which he is now wholly absorbed. Eco-criticism can best be defined as 'the study of the relationship between literature and the natural environment'. As a discipline eco-criticism has two main thrusts, the first being the analysis of the role played by the environment in literature where it is not the overt subject matter; Prof Wylie referred to the forest in a 'A Midsummer Night's Dream' to illustrate this point; other examples include the contrast drawn in Jane Austen's novels between tame gardens and wild countryside and, closer to home, the role of water as a symbol for religion in South African farm literature.

The second thrust deals with the increasing body of work documenting growing scientific awareness of the fragility of our eco-systems. In the 16th century Leonarda da Vinci warned that humanity poses a massive threat to both itself and to the survival of all species on the planet. Prof Wylie cites da Vinci as a visionary who understood how an equitable compassion towards animals would result in greater compassion towards our own species, and how humanity's ability to unite and to make art can only be understood when contextualised in its proper setting, including the ecological. This, of course, is where the concept of eco-criticism comes into its own.

Prof Wylie is an amusing speaker; he had the audience in stitches when he solemnly informed them that the danger of submitting a topic before writing the lecture is that concepts like the 'largesse of literature' then have to be interpreted. However, he presented a very good explanation; literature is everything we write, and it is all susceptible to eco-critical scrutiny. In turn, eco-criticism can be wielded from any angle, be it Marxist, feminist or other. Emotions about elephants run high, and discussion about them covers all aspects of environmental debate. One cannot, says Prof. Wylie, look into an elephant's eye and not wonder what they, looking back, are thinking about us. How we imagine them, and how we represent them, acts as a mirror, and tells us about ourselves. Phiosophers have suggested that we recognise a similarity in other species, which allows compassion to flow between our two different organisms. David Abram suggests that, in fact, consciousness and sentience is universal, and that we, and all other species, are situated within it, in effect corporeally immersed in the Earth's consciousness. This, says Prof Wylie, is not a new idea. Testimony from San tribesmen in the 1870's shows the tribal sense that animal and person were all one, a state of affairs which meant the healer of the tribe could inhabit the jackal with no sense of cognitive dissonance.

These notions should not be casually dismissed, Prof Wylie warns; such imaginings are essential to breaching the barriers between living creatures. Compassion is a difficult concept to define, even when we are referring to an emotion between humans, let alone between humans and two tonne elephants. He himself views compassion as synonymous with 'encompass' – it is a term which says “we are all on this journey together.”

How does our literature represent compassion? How does it colour how we react to other living things? All kinds of genres use elephants, from hunting literature to children’s fiction, from post-colonial writing to coffee-table books. Prof Wylie believes eco-criticism is a vital tool for analysing these many and varied representations, and therefore for informing how we treat the animals themselves. The discipline proposes new commonalities on which ethical treatment can be based. While we can never know, he says, what is in another animal's mind, we need to try to form a compassionate path, where our ethics can encompass these others, through our imagining of their needs.

Prof Wylie concluded with the statement that literature is a powerful vehicle for formulating such compassion, and that the need for it is given terrible urgency by the ecological catastrophe fast approaching. The evening closed with a reading of his poem “Where in the waste is the wisdom?” and prolonged applause from the audience.

Prof Dan Wylie's paper click here

By Jeannie McKeown

Picture: Prof Dan Wylie

Picture by Sophie Smith