NALSU director Prof Lucien van der Walt writes in the recent issue of Amandla magazine that discussions of workers’ education and union revitalisation are often framed in ways that pose the issues as simple organisational “fixes.” But the issue of workers’ education in union revitalisation poses the primary question: what is the aim? This is not a neutral, technical question, but profoundly political. If the aim is to build democratic, radical and transformative unionism, union education must be aligned with this aim. This requires a focus on building a strong union base that can exercise workers’ control of the union; fostering debate and critical thinking including exposure to a wide range of ideas and honest reflection on past approaches, including party politics; dealing with systematic theory as well as vocational and practical skills; and aiming at an autonomous, solidarisitic, transformative movement that fosters popular counter-power, class-based alliances, neighbourhood-linked education centres and direct action. This can prefigure a new society. The article is based on a plenary talk at the Michael Imoudu National Institute for Labour Studies, Ilorin, Nigeria, in 2019.

The full article can be read below or accessed here in the published PDF form [link]:

Building the union for the future - linking bottom-up workers education to union revitalisation

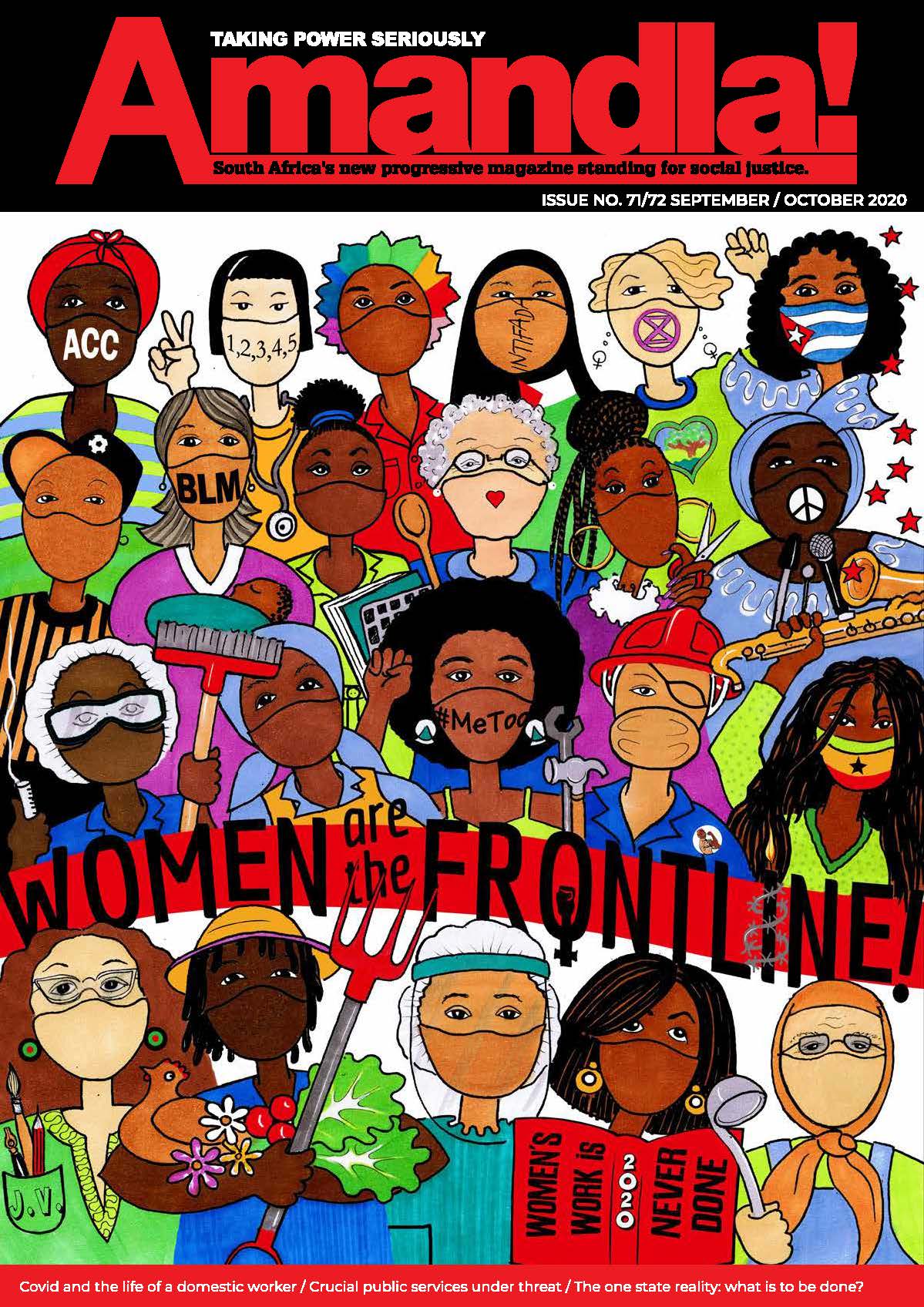

By Lucien van der Walt (2020), Amandla, number 71/ 72, pp. 32-34

This article is based on a plenary talk at the Michael Imoudu National Institute for Labour Studies, Ilorin, Nigeria, in November 2019.

DISCUSSIONS OF UNION education and union revitalisation are often framed in ways that pose the issues as simple organisational "fixes." But looking at the role of union education in union revitalisation poses the primary question: what is the aim? This is not a neutral, technical question, but profoundly political. What are the union's aims, its role and agenda? These shape what workers' education should be. This is not just a matter of the topics covered. It also involves the paradigms taught and methodology used.

If the aim is to build democratic, radical and transformative unionism, union education must be aligned with this aim.

Aims and means

First, this means an emphasis on building a strong union base, enabling meaningful workers' control over the union. Union education programmes must then emphasise empowering large layers of grassroots militants, in carefully constructed and systematic ways. The union, as an organisation, can then be protected (as much as possible) from decapitation by repression and co-option of leaders, and capture and corruption within its structures.

Naturally, workers' education is not enough to ensure workers' control: you also need democratic structures based on strict mandates with report-backs. There should be decentralised structures, including in finances, where some subscriptions must be retained by local branches. But democratic structures are not enough. You need to build consciousness, as any structure can be warped. So, education, then, includes class consciousness and fostering of a moral compass, based on solidarity, empathy, kindness and equality.

Workers' control, critical thought

Second, workers' education should promote critical thought. By this, I mean the ability to reason and analyse in an evidence-based, logical manner, not criticising everything for no reason.

A major problem from the 1990s was COSATU moving to a model of political education rooted in the top-down, Marxist-Leninist traditions of the South African Communist Party (SACP). The SACP secured, for the first time in decades, a premier role in mass, public union education. Let's be crystal clear: this education has delivered important insights, historical information and anti-capitalist analyses. The SACP and its tradition are key parts of the left and the working-class heritage, historical memory and struggles. But there are also limitations. Effectively, only one theoretical approach was presented; and within that approach, only one application of the ideas was stressed:

- Marxism-Leninism in the Congress tradition;

- The theory of Colonialism of a Special Type (CST) including white monopoly capitalism (WMC); and

- The associated strategy of National Democratic Revolution (NDR), led by the African National Congress (ANC).

Nuance and debate

There was little scope to clarify or evaluate arguments through real comparisons with other views, or to deepen understanding by locating the positions presented in the context of larger debates on the left (including within Marxism-Leninism), or the evolving ideas of the SACP. For example, the SACP's initial 1920s version of the CST/ NDR approach, backed by the Comintern, outlined a radical, SACP- led NDR. SACP leader Albert Nzula dismissed the ANC as national-reformist "good boys" in his book Forced Labour in Colonial Africa, written in Moscow.

Today, this nuance and complexity is missing. The current ANC-COSATU- SACP alliance is treated as a self-evident, inevitable advance. Historically, there were serious debates over the possibilities of a union-driven, class-based transformation of society, as advocated by the much-caricatured 1980s FOSATU "workerists". These have been reduced to stepping stones to the Alliance, as if the Alliance was the only possible outcome - or even the best one, which is by no means obvious.

This does not enable much in the way of exposure to deeper issues. Debates are reduced to strategy, with strategy limited to variants on the dominant model. One result: many know the phrases but are poorly equipped to seriously engage opponents. Others are unclear how theory can be applied to concrete situations, including tough workplace issues like retrenchments. So, radical theory co- exists with, but is quite separate from an economistic union practice.

Learning real lessons

Within this top-down approach, there is a temptation to measure success by the ability to remember the line, with little scope for debate or evaluation. This also undermines workers' control: official policy and resolutions are taught as truth, rather than as positions reached by healthy debate, in the best traditions of workers' democracy. If union congresses are workers' parliaments, there must be scope for more than one political tradition, and for debate and renewal within traditions. As Mandy Moussouris and I have argued in a recent paper, workers' education and workers' control are indissolubly linked.

The official line can be wrong. When there is no tradition of critical evaluation, the outcome can be disastrous for the union base: political disorientation when the line fails, or unthinking dogmatism, sloganeering and emotive politics, and personal loyalties that ignore facts that do not fit. Abstract theory and daily stagnation replace a lively workers' movement. For example, the failure of the Alliance is presented as due to betrayals, rather than to intrinsic problems in the model. Solutions then become fixing the Alliance, or creating a new party in place of SACP.

The top-down approach is vulnerable to leaders who impose personal agendas and views, without the processes essential to democratic unionism. This is a recipe for personality cults; the correctness of a line is measured by who speaks. The flip-side is debate by labelling and personal polemics. At one point, COSATU conceded some of these issues. The 2009 political report argued for a dynamic socialist movement that would "draw on many forces in civil society…while we differ with some of the theoretical, strategy and tactics of the Troskyites and Anarcho-Syndicalists… it will be folly to ignore some of their valuable critique." This has not come to pass: intolerance, even within the narrow NDR model, became the norm in COSATU and in its splinters.

Radicalism plus heterodoxy

Third, workers' education should expose people to radical ideas, while practising heterodoxy i.e. critical engagement with, and exposure to, a range of views and theories. That includes views people might not like. Participatory techniques are essential, but not a substitute for this material. It is both abstract and systematic, so it cannot simply be formulated from personal experiences. It is built up from debates, events and information that go well beyond any individual experience, and entails systematic syntheses i.e. theories. We can and should link theory to experience, but it is not reducible to experience.

For example, we live in the neoliberal epoch of capitalism. To understand neoliberalism, we must understand liberal economics, the neoclassical theory that underlies it. This deepens understanding of its logic, and of why it appeals to many as common-sense. Thinking we understand it through slogans, crude statements, experience or intuition will not do.

Heterodoxy means opening up the rich treasure chest of working class and left history, including traditions like anarcho-syndicalism and Marxism. Most union economic proposals in South Africa are actually based in Keynesian social democracy (sometimes rephrased in NDR language), but we can't see this orthodoxy if we do not take theory seriously. Then the Keynesian project can be named, and evaluated as theory and historical experience.

Debate and difference are healthy, and there is nothing to be afraid of in discussing different views. What we should be afraid of is a culture of intolerance, vanguardism and manipulation. It presents itself as revolutionary when in fact it is a death sentence for a democratic, bottom- up, transformative unionism.

Breaking their haughty power

Fourth, workers' education should be part of a transformative project. Any reasonable evaluation of the current situation indicates the need for profound change. It shows we operate in a world where a small ruling class dominates and exploits the popular classes through two pyramids: the structures of state and capital. Wealth and power are centralised. That is why natural endowments of wealth, like oil in Nigeria and gold in South Africa, or rapid economic growth, simply do not lead to better conditions for most people. This is true whatever the colour, nationality or gender of ruling elites.

It must be debated whether the state can actually be used by the popular classes. This claim can be tested against facts and experience. The claim that the state can or does represent the people is a fiction, easily dispelled by critical thinking. States operate by an iron logic of domination and resource extraction, by and for a few.

Similarly, the argument that "capitalism can deliver" can be evaluated using theory and facts. Capitalism is revealed as a wasteful, inefficient, exploitative, crisis-ridden system; its innovations a profoundly distorted form of development, just as state government is a profoundly distorted form of administration. Capitalism cannot be changed by entrepreneurship from below, or displaced by cooperatives, or transformed by petty trading, or a solidarity economy. This is because these initiatives exist on its margins, often as the desperate efforts to survive of hundreds of millions of poor people worldwide.

Counterpower, counterculture

This would suggest that the union movement needs to be the opposite of capital and the state:

- Bottom-up rather than top-down;

- Inclusive and democratic, rather than exclusive and exploitative;

- Solidaristic and inclusive rather than intolerant;

- Uniting workers in unions, uniting unions with each other, including across borders, as well as unions with other popular class sectors, like tenants in poor neighbourhoods, peasants, petty traders, unemployed etc.

Such a movement can develop the power to resist the existing system, and create a new society that is very different.

It can build a counter power to the existing system, with mass organisation that can take direct power by capturing and collectivising major means of administration, coercion and production. That can take over, and govern society through participatory democracy, including self- management at work, and participatory planning, including of production. It means preparing the popular classes for power through mass organisation, not handing it over (again) to parties, politicians, guerrillas, demagogues, dictators, or imperialists.

Technical and vocational skills

Union education should also try to develop technical skills, including accounting, planning, writing etc. We need to carefully study and map the industries and sectors where we organise. This is key to the whole project of taking over through a revolutionary, or social, general strike.

Every effort must be made to maximise popular access to vocational training.

Some dismiss this as not radical enough. However, slogans will not substitute for practical know-how; a lack of skills inevitably means bringing back top-down management. Others favour vocational training to upgrade workers for better jobs. But if vocational education is not embedded in the larger transformative project, it boils down to career advancement for a few. There is nothing wrong with such advancement, but most people will not access better jobs, and accessing better jobs does not emancipate society.

The sites of education

Finally, the sites of workers' education matter. Institutionally, we need to build up specialised, well-resourced education structures, guided by congress decisions rather than direct control by a few leaders or funders. We need to rebuild equitable partnerships with labour service organisations.

Geographically, experience shows the value of building a large network of neighbourhood-based, or neighbourhood- adjacent centres. These can double as meeting places, and allow the education to include those not directly within union structures, such as housewives, unemployed and youths. This expands the reach of the project of building a radical counterculture. It creates a space for joint mobilisation and for unions to play a direct role in community politics and organising (e.g. among tenants or in social defence) and to transfer union skills and democratic structures into communities.

This extension of counter power is an important class-based alternative to parties, party militias and patronage, and reactionary ethnic, racial and national mobilisation.

Beyond workplaces

What matters is building a set of counter institutions, ideological, educational and organisational. They include unions, popular schools, social centres, tenant movements, self-defence groups, clinics and cooperatives. They must be autonomous from the state and capital. They must be able to prefigure a new society through building counterpower and counterculture. They must enable massive redistribution of wealth and power through direct action and participation, creating needs-based, egalitarian, common ownership-based, universal human community. There is a need to resonate with the larger society, and that means we should not reduce union work to workplace or wage issues

The issue is often raised here about union resources: can unions afford this? That is not a simple economic question. It is rather a profound question of politics, about how unions allocate resources. As an example, many South African unions have billions of rands of investments in the private sector, yet they complain about a lack of education resources. Unless you are aiming at a more expansive unionism, more democratic and more transformative, questions of resources and partnership will be side-tracked into discussions of revenue. Unions tying up billions in capitalist companies reveals a profound failure of politics.

In short, I am advocating a reformed, transformative unionism based upon the very best of historic labour movement practice. This includes African unions; it also includes anarcho-syndicalism, which today continues to influence struggles, including in Rojava, Syria, where a profound democratic, ecological and feminist revolution is taking place, right now.

**Lucien van der Walt has long been involved in union and working-class education and movements. Currently at Rhodes University, he's part of the Neil Aggett Labour Studies Unit and the Wits History Workshop.