South African higher education institutions ought to raise awareness and condemn rape culture to challenge and deconstruct the harmful ideologies many students enter universities with. According to Fanflik (2007) rape has many physical and emotional reactions such as, but not limited to: aches and pains like head; back and stomach aches; heart palpitations; changes in sleeping patterns; appetite and interest in sex; fear; grief; outbursts of anger; intrusive thoughts of the trauma; nightmares; feelings of helplessness; attempts to avoid anything associated with the trauma; tendency to isolate oneself; difficulty trusting; feelings of self-blame and shame. This shows that rape has countless physical and psychological consequences and could take months or years to heal and asking questions that endorse rape and blaming the victim further traumatised the victims.

The aforementioned physical and emotional consequences faced by survivors consequently deters them from reporting incidences of rape further exacerbated by a lack of faith in the criminal justice system, the medical service providers and negative attitudes reproduced by the university community. This points to a dire need for institutions of higher learning to formulate and instil policies pertaining to the reporting and monitoring of incidences of sexual violence. Due to the lack of efficient reporting structures, there is a tendency for the re-victimization of students who do attempt to report such incidences (Whitfield).

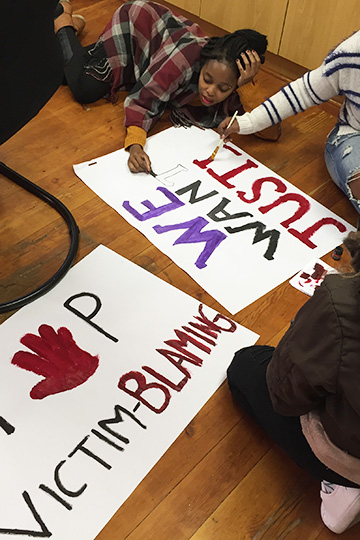

Mismanagement and secondary trauma has led to student groups feeling forced into taking matters into their own hands. The best-known case of this is the #RUReferenceList protests, which occurred in response to the publication of a list of alleged perpetrators of sexual violence at Rhodes University, some of which remained on the Rhodes University campus despite serious allegations which were not investigated. The list was shared on social media and became a rallying point for unhappy students aimed at what they felt was the university’s inadequate sexual violence policies. These students believed the policies perpetuated victim-blaming and protected the perpetrators of sexual violence (Whitfield, 2017).

Victim blaming forms a large part of rape culture, rape culture is the ongoing normalisation of rape and sexual abuse, in which victims are discarded, rapists are excused, and the pain and suffering caused by rape is trivialised (Johnston, 2016). For example, rape culture is asking problematic questions such as “what was she doing?”, “what was she wearing?”, “why are you reporting it now”? why were you out at night? And “was she drunk”? such questions normalise the raping of women by way of implying the acceptability of men sexual violating women because she was out at night, she was drunk and she was wearing revealing clothes.

Hockett, Saucier, and Badke (2016) argue that rape myths that suggest that rape ought to look a particular way i.e. perpetrated with the use of physical and usually violent coercive means (e.g. using a weapon, leaving bruises) and that women who are sexually assaulted while under the influence of alcohol intoxication are at least somewhat responsible for letting things get out of control. These beliefs deny the existence of sexual violence unless obvious indicators of force are manifestly evident and justify sexual violence by suggesting that the behaviours of the woman who was raped may have invited the rape.

Moreover, false beliefs about rape, defined as beliefs that individuals have about what is stereotypically constitutes an incident of rape. These beliefs are called “rape scripts” and they basically present an “ideal victim” image, often including the assumptions that rape is always a spontaneous and violent attack against a chaste, non-intoxicated, and otherwise “respectable” woman by a stranger in a deserted public location, culminating in manifestly violent sexual intercourse (Hockett, Saucier, & Badke, 2016). This suggests that if the experience of the sexual assaulted is not as the “ideal victim image” it’s not rape. The rape myths and rape scripts are reciprocally reinforcing, defining rape more narrowly than it is reflected in law and such beliefs normalise rape determined how effectively the case will be handled.

According to South African lawrape is defined as forcing a person to have sexual intercourse, oral, or anal sex, against their will or by using force, threatening to harm that person, or a third person. Penetration, no matter how slight, is necessary to call the act rape; ejaculation is not necessary. Penetration may be of the vagina, the mouth, or the anus, and may be by the penis, other body part or an object (Dworkin, Buchwald, Fletcher & Roth, 1993). In other words, lack of consent is crucial to the definition of rape and consent must be clear, unmistakable and voluntary agreement between people to participate in a sexual activity.

Also, someone cannot consent if they are asleep or under the influence of alcohol or drugs and everyone has the right to stop any sexual activity whenever they want, regardless of what has happened up until that point, or in previous sexual encounters (Dworkin et al., 1993). This implies that any time you say, “no” to intercourse and it is forced on you, that is rape. It doesn't matter if you said “no” in the middle of the act, it is still rape if the other party doesn’t immediately stop and respect your wishes. Therefore, communication before, during and after sexual activity is extremely important to make sure that everyone is comfortable with what is happening and is consenting throughout.

In conclusion, South African universities need to psycho-educate students about what constitute rape and learn how to better and more empathetically manage reports of sexual assault so that students stop to have their constitutional rights violated in the place they go to learn and grow.

References

Dworkin, A., Buchwald, E., Fletcher, P., & Roth, M. (1993). Transforming a Rape Culture. United States of America: Stanton Publication.

Fanflik, P. L. (2007). Victim responses to sexual assault: Counterintuitive or simply adaptive. American Prosecutors Research Institute.

Hockett, J. M., Saucier, D. A., & Badke, C. (2016). Rape myths, rape scripts, and common rape experiences of college women: Differences in perceptions of women who have been raped. Violence against women, 22(3), 307-323.

Johnston, C. (2016, May) Rape Culture at Universities. Sun. Retrieved from http://www.sun.ac.za/english/Documents/In%20the%20news/2016%2005%20May/09%20May%20-%20Perdeby%20-%20Rape%20culture%20at%20universities.pdf.

Whitfield, K., (2017) Op-Ed: Education and policies are vital in fight against rape culture. Daily Maverick. August 10, 2017, from https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2017-07-25-op-ed-education-and-policies-are-vital-in-fight-against-rape-culture/#.WYjGUumxXIU.