Human Rights Day seems an apt moment to reflect on the life of Imam Abdullah Haron, murdered by Apartheid police in 1969. Both his story and his contribution have been forgotten by many, but the re-publication of his biography, banned when it was written, is aiming to change that.

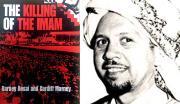

The Killing of the Imam, by Barney Desai and Cardiff Marney, was originally published in 1978, and promptly banned by Apartheid censors. The new edition was brought out by the Imam Abdullah Haron Education Trust late last year, with the idea to re-publish the work coming from a charity event two years ago where Cape Town mayor Patricia de Lille donated her original copy to be auctioned. The trust realised that very few copies of the book were available in South Africa, and subsequently determined to bring out a new edition – with proceeds going to the trust’s early childhood development programme.

Haron’s name is not often heard today, but the imam was one of the most prominent Muslim clerics of his day, known for his political involvement at a time when many Muslim leaders were silent about Apartheid’s injustices. As the book’s preface notes, Muslim leaders did not make any public statement about Haron’s murder by the Security Branch: “they were, understandably, all extremely afraid”. But Haron never let his fears outweigh his integrity.

Haron’s formal education was limited to primary schooling only: a fact to which the authors attribute his passionate pursuit of education for his own children. His was an extremely religious upbringing: Haron was brought to Mecca by his mother three times, a momentous financial outlay for a poor family, and he could recite the Quran off by heart by the age of 14.

When he was appointed Imam of the Al Jaami’ah mosque in Claremont at just 32, many were sceptical, given his youth, his impish sense of humour and the fact that he “wore his black fez perched at altogether too-fashionable an angle upon a controversially clean-shaven head”. He could also only manage to make the second team for the Watsonias Rugby Club: Desai and Marney suggest mischievously that if he’d been playing for the first team, he might have found it easier to win the instant support of his congregation.

But Haron quickly put misgivings to bed through his simplicity and modesty: winning admiration, for instance, for his refusal to accept the customary fee for performing wedding ceremonies or funeral rites. Under his leadership, the mosque established women’s work and study circles, and raised funds for the poor. He became a major talking-point in the South African Muslim world when he declared that his mosque could not be shut down, as was threatened by the Group Areas Act, because Quranic law specified that the mosque building was inviolable.

Haron specialised in socially relevant religious teaching, and he had a perfectly practical reason for this: he wanted to make progressive and intelligent young Muslims feel they had a home, so they wouldn’t leave the Islamic fold. Nonetheless, his political awakening didn’t happen overnight: it was only after about 1960, when he was 37 years old, that Haron began to take an active interest in Apartheid’s resistance movements. This was partially sparked by his decision to take the teachings of Islam to black migrant labourers. Here, the authors record, he “discovered an impatience for and a confidence in national liberation such as he had not previously encountered.”

Sharpeville was a game-changer for Haron. Shocked by the events, he became part of a movement which smuggled food and other supplies into townships – an activity which earned him the scrutiny of the security police for the first time. He began to develop close relationships with leaders of the Coloured People’s Congress (CPC), calling on his congregation to support their strikes. “Slowly his religious and political concerns began to come together in the struggle for liberation,” the authors write.

In March 1966 the CPC disbanded with instructions to its members to join the PAC, an organisation that Haron was already familiar with because he found its ranks surprisingly fertile ground for missionary work. This was a tipping point in terms of his personal safety: “he was now a member of a party dedicated to the overthrow of Apartheid by all means at its disposal, including violence”.

Haron’s activities were not limited to the country’s borders. He was instrumental in lobbying members of the World Muslim Council to seek help from their governments in intervening in the South African situation. He also produced leaflets to be distributed to South African Muslims on hajj to Mecca, reminding them that their duty as Muslims required them to help fight Apartheid when they returned home. After being contacted by a colleague in exile, he met Canon John Collins, of St Paul’s Cathedral in London, and agreed to work together with the Christian cleric to raise financial aid for the victims of Apartheid.

By this stage Haron was under constant police surveillance, and treated to countless impromptu visits by the police at both his home and his mosque. Fortunately Haron’s day job as a sales manager allowed him to move across the country without attracting much suspicion, but by 1967 he had already been arrested once. Alarmed friends urged him to go into exile, and his employers indicated their willingness to transfer Haron to an overseas branch, but Haron knew his work was in the country of his birth. On 28 May 1969 – the birthday of the Prophet – Haron was summoned to Caledon Square for a chat. He would never leave police custody.

Haron’s failure to give his interrogators what they demanded resulted in his arrest under section 6 (1) of the Terrorism Act of 1967, which allowed for detention for an indefinite period. The inquest into Haron’s death revealed that the imam was subjected to “constant interrogation daily” throughout the month of June. In particular, police wanted him to talk about his trips overseas – to Mecca, London and Cairo – where they alleged that he had met up with terrorists and conspired against the government. They also believed that the Ibadurahman Study Circle which Haron led was a political organisation.

On the outside, it was known that Haron had been arrested. Catherine Taylor, a United Party MP, several times questioned the minister of police as to Haron’s whereabouts and the reason for his detention. The minister replied that it was “not in the public interest” to answer her questions.

After being beaten almost to the point of unconsciousness by police, Haron was taken to the Bellville district surgeon on 29 June. The doctor, Dr Viviers, “had a policy which commended him to security policemen: he never questioned political prisoners too precisely.” Despite his injuries, Haron was sent packing with a few pain pills. A few days later, Haron was again savagely attacked in his cell. Another doctor was brought in – another one who didn’t cause trouble with the police – and he resolved that Haron was suffering from flu.

Despite his beatings, Haron steadfastly refused to release the names and details of his old colleagues. On 11 August he was moved to a police station in Maitland, but 10 days later he was taken back to Caledon Square for the day for further interrogation. This time, his attackers attached electrodes to his genitals and shocked him until he passed out. On 17 September 17 he was again brought to Caledon Square. On this occasion, “they brought in a beam of wood and rested this on high stilts. Haron was instructed to place his right leg over the beam, with his knee almost touching his chin. His left leg almost buckled under the strain. The mystery-men then came up behind him and deftly inserted a needle into the lower part of his spinal column.”

After days of torture, Haron was continually plagued by a splitting headache, exacerbated by being deprived of food. He begged for a doctor but was denied one; his food supply remained erratic. With his physical condition rapidly deteriorating, a few days later the duty constable offered him a doctor, but Haron refused. “He had now given up hope,” the authors write. “A request for a doctor would only mean another visit from the security police, and they were the last people he wanted to see.”

On the morning of 27 September 1969, Imam Abdullah Haron died. Hours later, his wife Galiema was informed by the security police that her husband had had a heart attack. There were 30,000 mourners at Haron’s burial: “The vast assembly, gathered to show its esteem for the dead Muslim priest, turned into a spontaneous demonstration against the government and its police force, as speech after speech at the graveside abominated Apartheid and its agents.” Haron’s death was discussed in the UN, and a martyr’s send-off was given to Haron at St Paul’s Cathedral, where for the first time ever, a Muslim recited verses from the Quran.

At the inquest into Haron’s death, police argued that Haron had sustained the numerous bruises evident on his body from slipping and/or falling down a flight of stairs. The advocate defending the interests of Haron’s family, a Mr Cooper, argued that Haron “died as a result of a heart attack which was triggered off by trauma”. The judgment of the magistrate found that Haron died of “myocardial ischaemia…due to, in part, trauma superimposed on a severe narrowing of a coronary artery.” He found that “a substantial part of the said trauma was caused by an accidental fall down a flight of stone stairs.”

The Killing Of The Imam is a slim book, and more than half is devoted to a reconstruction of Haron’s time in detention. While this is chilling and important reading, the book’s introductory chapters play an equally useful function in serving to humanise the imam. We learn, for instance, that he loved James Bond and had an entirely questionable dress sense as a youngster, favouring “lurid bow-ties and the widest possible flared trousers”. His murder was one of many Apartheid tragedies, and for his life to be forgotten would be another.

Written by: Rebecca Davis

Picture credit: Daily Maverick

- Rebecca Davis studied at Rhodes University and Oxford University. This article was published on Daily Maverick.