A new stem cell technique could regrow organs that the body will not reject and is an important step towards a cure for diseases such as Alzheimer’s and injuries such as spinal cord trauma. (AFP)

It is "incredibly exciting", says Professor Michael Pepper, director of the Institute for Cellular and Molecular Medicine at the University of Pretoria, adding that it is not a question of "whether the technology comes to South Africa, but when".

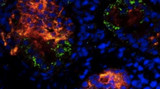

Scientists at the Oregon Health & Science University and the Oregon National Primate Research Centre on Wednesday announced in a joint press release that they had succeeded in "[reprogramming] human skin cells to become embryonic stem cells capable of transforming into any other cell type in the body".

This means that the stem cells – used for therapeutic rather than reproductive purposes – contain the same genetic matter as the person they are being put into and will not be rejected, says lead researcher Shoukhrat Mitalipov.

It is based on a technique called somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT), which involves transplanting the nucleus of one cell, with the donor's DNA, into an egg cell that has had its nucleus removed. The Oregon-based researchers used unfertilised eggs.

Although SCNT is not new, stem cell specialist at the University of Cape Town Professor Susan Kidson says that "the derivation of viable embryonic stem cells from this embryo is something scientists have been battling with for a while".

Genetic material

Pepper distinguishes between adult stem cells and pluripotent stem cells, which include induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), which are cells that can also be manipulated into becoming liver cells or heart cells, for example. John Gurdon of the Gurdon Institute in Cambridge and Kyoto University's Shinya Yamaka won the 2012 Nobel Prize for physiology or medicine for discovering that mature cells could become pluripotent – in other words, mature cells that have the capacity to become other cells.

Although iPSCs offer "huge therapeutic potential, the technology involves the introduction of new genes into the cell to make them pluripotent", Pepper says.

The difference between SCNT and this new technique is that the American researchers have generated primitive stem cells that have the genetic material of the donor, and therefore, because the donor and the recipient are the same person, the cells will not be rejected.

According to the researchers and South African experts, this new technique is important for two reasons: it uses a patient's genetic material – so it will not be rejected, which can happen if another person's DNA or cells are involved in the process – and it does not use a fertilised egg or an early embryo, thus removing concerns about the ethics surrounding the origin of the cells.

Mitalipov also notes that it is unlikely that this technique would be able to be used for reproductive, rather than therapeutic, cloning. Human cloning is illegal in most countries in the world.

When asked whether South Africans would see this technology, Pepper says: "We see everything in South Africa; when is the question.

"A drawback is that the technology is not simple – but that's not a long-term problem. It gets easier as it develops."

By Sarah Wild

Sarah Wild is an award-winning science journalist. She studied physics, electronics and English literature at Rhodes University in an effort to make herself unemployable. It didn't work and she now writes about participle physics, cosmology and everything in between. Read more from Sarah Wild Twitter: sarahemilywild

Article Source: Mail & Guardian