Nelson Mandela, generally viewed as the embodiment of South Africa’s democracy, was not always the genial, open-minded fatherly figure whose smiling face is associated with the hopes that many cherished for the new South Africa.

As the titles of Mandela’s books indicate, his life comprised a series of journeys; the first being called No easy walk to freedom (borrowed from Jawaharlal Nehru) and his autobiography, Long walk to freedom. The notion of a journey figures prominently in mythology, especially associated with masculine heroism.

Mandela’s journeys entailed both changes in his physical location but also his status in life; married, divorced, remarried, training to be counsellor to a future Thembu king, runaway to the Witwatersrand, country hick on the Rand, dapper lawyer, boxer and militant political actor.

Mandela sees himself possessing full freedom in his early life in Thembuland where he encountered few whites, but from the 1940s he learns otherwise in Johannesburg. In the 1950s he and other ANC leaders operate partly legally and partly outside the law. He leads the Defiance campaign of 1952 and is in the forefront of the M-Plan to prepare the organisation for operating underground.

When placed under restrictions, he continues his political activities in conditions of secrecy, as did Albert Luthuli, Walter Sisulu and others. Long before the decision to launch MK, Mandela and Sisulu resolved to request support for armed struggle from the Chinese, which was refused. It is clear that some time before his imprisonment, Mandela lived in the shadow of that possibility.

The notion of journey does not mean that having been one thing, Mandela became something else without retaining any qualities deriving from what he had been before. His life comprised both ruptures and continuities. He left Qunu early in life, but returned in his retirement. He became an African nationalist then a believer in non-racialism, and some evidence shows also communism. But appearing in court in 1962 he wore abaThembu attire, asserting that a person could be an African nationalist without abandoning other identities.

In the period prior to his arrest Mandela often acted out of anger, inciting people to violence, without any organisational mandate. The prison period was important in Mandela’s development for it was here that he says he ‘matured’, meaning learning to restrain the anger and sometimes-impetuous conduct of his earlier days. He had been willing to fight when the doors for peaceful struggle had been shut in the face of the black people of South Africa, becoming the first commander of MK. But when the opportunity for peace presented itself Mandela grasped it.

Mandela admits that he consciously chose not to consult others, for he would have been stopped. This is part of a general feature in Mandela’s political life, manifesting an ambiguous relationship to collective decisions. It was only when Sisulu became secretary-general in 1949 that the ANC adopted collective decision-making. Mandela repeatedly found himself on the wrong side of the collective in making various unmandated statements.

In initiating talks, Mandela was no longer the hot-headed young man of the 1950s but a person who believed he had to break the deadlock in a situation where neither side could defeat the other. In beginning discussion with ‘the enemy’ Mandela understood the risk to his reputation: that he could be labelled an opportunist or a ‘sell-out’ or an ‘individualist’, as has happened. But if talks were initiated, they had to be in secret. Once accepted in principle, Mandela made it clear that it was not for him but the ANC to negotiate.

While the Mandela who originated the process was not the angry young man of the 1950s: that anger could resurface when he believed he was betrayed, as was sometimes the case with the last Apartheid president, FW de Klerk.

In preparing South Africa for democracy, which he would lead, Mandela also consciously readied himself for a role suited to a country torn by divisions. There was nothing spontaneous in Mandela’s gestures of reconciliation. He knew it was necessary to reach out to those who feared or might resist democratic rule. Much, as some ridiculed his tea with Betsie Verwoerd or his wearing a Springbok rugby jersey, he did what he considered necessary to secure the peace.

Nelson Mandela could be extremely obstinate, as Sisulu repeatedly reports. But he was also willing to change, where the cause of freedom required. What we also learn from Mandela, amongst many others, is that he was not born with any of the qualities that we now associate with him.

As he himself says, he learnt and had to prepare himself to have the courage to face danger and death, to reach out to the oppressors, and to make various compromises. At the same time, the tough boxer always had a tender side, as manifested in his love of children. To learn from Mandela is not to consider a simple set of rules, but requires studying the lessons of his life.

By: Raymond Suttner

Professor Raymond Suttner, attached to Rhodes University and UNISA, is an analyst and professional public speaker on current political and historical questions and questions of leadership. He writes a regular column and is interviewed weekly on Creamer Media’s Polity.org.za. Suttner is a former political prisoner and was in the leadership of the ANC-led alliance in the 1990s. He blogs at raymondsuttner.com.

[This article first appeared on Creamer Media’s www.polity.org.za]

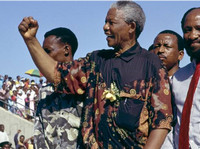

Photo: Bophuthatswana homeland, South Africa, 1994. Nelson Mandela is greeting jubilantly by supporters in 1994 during his campaign that spanned the country and saw him win the first ever democratic non-racial elections in South Africa. (Greg Marinovich)

Source: Daily Maverick