Institutions that have different mandates and duties - and co-operate with

one another - will best serve South Africa, write Adam Habib, Peter Mbati

and Mahlo Mokgalong.

Too many have chased the elusive goal of evolving into a research intensive

university Among the ideas being considered is rethinking degrees beyond

institutional boundaries.

A differentiated higher education system is a prerequisite for economic

competitiveness and inclusive development. The best exemplar of this is

Finland. The country does not have a single university in the top 50 of any

of the global ranking systems - yet it consistently tops the competitiveness

ranking and the human development indicator charts.

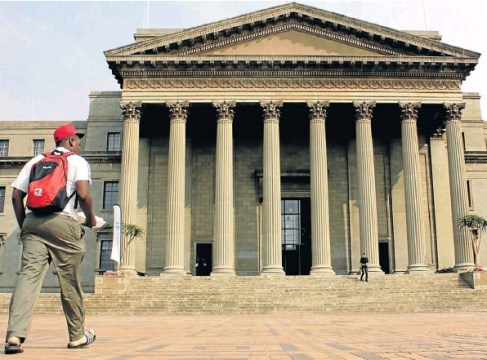

Wits is investigating ways of producing graduates jointly

with Limpopo and Venda universities.

That is because Finland's educational institutions are differentiated, each

with different mandates and responsibilities, independent and yet connected

to one another, thereby creating a seamless system that is both nationally

responsive and globally competitive.

A differentiated higher education system enables responsiveness to the

diverse and multiple needs of an economy and a society. This model is

particularly relevant to the developing world, where the demands of the

knowledge economy and social needs remain underdeveloped and therefore

require dedicated focus and attention.

In South Africa, it would allow some universities to play a bigger role in

the teaching of undergraduate students and the production of professionals

to meet market skills demands, which is necessary to improve economic growth

and competitiveness. It would also allow other universities to focus on

postgraduate students and undertake high-level research, which are equally

essential if we are to develop a knowledgebased economy.

And then, yet again, this higher education system should have a further

education and training sector comprising colleges focused on producing

graduates with vocational and applied skills.

These different responsibilities require very different skill sets,

institutional environments and investment patterns. This is why they cannot

simply be done by a single type of institution or university.

Why is it that South Africa has not been able to explicitly progress towards

a differentiated higher education system?

The answer, of course, lies in our history, which has saddled the evolution

of our system and our current choices with the burden of a racialised

legacy.

Too many higher education leaders in the post-apartheid era have wanted to

transform their institutions into what they had been prevented from becoming

in the apartheid era. Not only has this proved to be impossible, given the

scarcity of the resources available and the long time frame required to

mould universities and higher education institutions, but it has also

paralysed the system.

To get ourselves out of this impasse, we need to rethink the debate and

fashion the establishment of a differentiated system on four distinct

principles.

First, it must be underscored that the research enterprise must be common to

all universities. Even the universities primarily focused on the teaching of

undergraduate students must be engaged in research.

Otherwise, how else can they guarantee that their academics are at the

forefront of - and teaching the latest developments in - their disciplinary

fields? The only difference between these institutions and the more

research-intensive ones should be the quantity and extent of the research

obligations and, perhaps, the type of research activities.

Second, South African university executives and policymakers need to rid

themselves of a status conception of the university system, according to

which research-intensive institutions are seen as more illustrious than

their undergraduate teaching counterparts. Global ranking systems have

fostered this illusion, further burdening the imagination and ambition of

university executives, and the result is that too many have chased the

elusive goal of evolving into a research-intensive university.

Third, the financing of universities must not implicitly assume this status

hierarchy. Too often, executives at the research-intensive universities have

simply assumed that they should be the recipients of a larger largesse of

funds.

In fact, executives at researchintensive universities often make the

argument that one cannot turn the clock back on the history of privilege

that enabled only some of our institutions to evolve into research

universities, and that South Africa should position these institutions

through the generous provision of resources to compete with their

counterparts elsewhere in the world.

The assumption is that larger resources would be directed to these

universities. This argument was, of course, contested by historically black

universities, which use their history of disadvantage as a leverage to make

a claim for a bigger share of the resources. The effect was an implicit and

explicit fight for who is entitled to a bigger share of what was effectively

a dwindling higher education pie.

Finally, our higher education system must be flexible enough to allow

institutions to progress from one institutional variety to another, should

they so decide. Societies and their needs change over time and institutions

must be given the right to evolve in order to become responsive to these

needs. Moreover, allowing for institutional evolution enables university

executives to be more pragmatic in their decision-making since their

institutions are not forever closed off from being one or the other

institutional type.

But, however well we implement these principles, we are unlikely to make

progress in this regard so long as our universities and higher education

institutions do not learn to partner and work with each other.

These partnerships must be explicitly directed to breaching and overcoming

the racial and linguistic boundaries that defined the evolution of the

higher education system. And they must go further than simply formal

interactions. The partnership must involve the very core activities of the

universities and be directed towards joint degrees, combined teaching

programmes, joint research initiatives, support for the building of

institutional capacity and enabling the mobility of staff and students.

We, at the universities of Limpopo, Venda and the Witwatersrand, are

experimenting with how this can be done. Our institutional executives have

already met to identify potential areas of collaboration. Further meetings

are planned with both executives and academic staff members. Among many

ideas being considered is the possibility of innovatively rethinking degrees

beyond institutional boundaries so that we jointly can produce graduates

with skill sets needed by the South African economy.

For example, Wits's engineering faculty is considering working with Limpopo

and Venda's science faculties to bridge the knowledge gap by sharing skills

and expertise. Graduates from either a particular stream in these faculties

or those who graduate with a particular pass may get direct entry into the

third year of Wits's engineering programme.

This would allow these graduates to then earn both a science degree from

Limpopo and Venda and an engineering degree from Wits. Should we succeed in

doing this, not only would we have enabled a seamless movement between our

institutions, but we would have also jointly produced graduates with skill

sets urgently required by the economy and society.

Other, similar ideas are being thought through in our engagements. The

driving force in these engagements is a philosophical and strategic

realisation among all our people that we will never truly transform our

higher education system and the racial and unequal legacies bequeathed by

apartheid as long as we do not have the courage to proactively breach our

institutional boundaries and partner with each other.

In this sense, we see ourselves as more than simply academics; we see

ourselves as pioneering foot soldiers in a broader struggle to transform

higher education from its binary racial divides into one that is

differentiated, nationally responsive and globally competitive - and one

that we all can collectively be proud of.

Article by: Adam Habib, Peter Mbati and Mahlo Mokgalong.

Article Source: The Sunday Times.