A new centre at the University of the Witwatersrand that focuses on South Africa's vast fossil wealth underlines our position as world champs in palaeoscience.

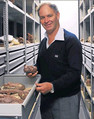

Oliver Roberts spoke to its ardent director, and was not bored E are shuffling along halls of shiny beige linoleum, talking about things that happened 350 million years ago, and Professor Bruce Rubidge, whom I later see is wearing colourfully striped wool socks under his dark-grey slacks, is worried that he is boring me.

"I don't know if I'm boring you," he keeps saying. And I keep assuring him that, no, he most certainly is not. Already this morning I have heard about the professor's childhood in Nieu Bethesda, how his uncle lived next door to that tormented owl lady Helen Martins and how, when the boy Rubidge went around back to play with his uncle's rabbits, he used to peek over Martins's wall and she would see him and run back into her house.

Already this morning Rubidge has interrupted himself as he is telling me stories like this and said: "Anyhow, we're not talking about that; we're talking about more exciting things —fossils." Already this morning I have held a small dinosaur skull in my hand, looked into its hollow eyes and trailed my fingers along its rows of perfect, perfect teeth. I am not bored.

Rubidge is taking me on a tour of the University of the Witwatersrand's palaeoscience Centre of Excellence, which opened recently and of which he is the director. The centre's purpose, officially called "the South African strategy for the palaeosciences", is to ensure the protection, preservation and development of the astonishing fossil wealth this country possesses, both in the thousands of radical finds that sit in our museums and universities and all the ones that still await discovery.

The centre is the result of two years of research and planning and is funded by the departments of science and technology and arts and culture, as well as the National Research Foundation. The collaborating institutions are the University of Cape Town and the lziko Museum in the city, the National Museum in Bloemfontein, the Albany Museum at Rhodes University and the Ditsong Museum in Pretoria.

Rubidge, who is standing before a large map that shows all the locations where esteemed palaeontologist James Kitching uncovered decisive fossils over 23 years of relentless digging, says the centre is somewhat of a rescue act.

"We always struggled to get What has been found here, under land and inside dark, dripping caves, has pretty much charted the entire saga of humanity funding for palaeontology during the apartheid years, and it's still difficult, because it doesn't fit nicely in the government funding system for universities," he says.

"We rely on quite a big team of technicians and the funding system can't support it, and that's why the centre is an absolute saviour to us." Look, we all know that South Africa is a palaeontologist's wet dream. What has been found here, under the earth and inside dark, dripping caves, has pretty much charted the entire saga of humanity.

The specimens that we have uncovered, and continue to dig up, are truly, shockingly revolutionary. Places such as the Cradle of Humankind and the Wits Origins Centre remind us of this. But to really, really comprehend the absurd profusion of fossil treasures that we have you need to stroll beside a long table that is laden, absolutely laden, with all the fossils unearthed during a recent two week dig in Beaufort West in the Western Cape.

I am thinking there has been some kind of mistake; it is some kind of palaeontological gag. But Rubidge says: "We can collect an average of 30 fossils a day. After every rain things open up. Textbooks say that for every million animals that die only one becomes preserved as a fossil.

And, if we are walking around picking up 30 of these a day, it gives you an indication of what's around." They are all spread out, the fossils, and attached to each is a tag with information about the exact location it was found, as well as speculative, question marked labels about what species it might be.

The fossils are still in their raw form, barely visible, because they are still married to the rock. Later, the remains will be taken to the room in which we are now, where staff are hammering and chipping and carefully eroding the rocks with tools that sound like dentists' drills, until this thing, this creature, frozen like a photograph, surfaces.

"Here's a piece of a dinosaur," Rubidge says, holding a large slab of stone. "There's the eye; there's the back of the skull over there; there's the nose and underneath here are some teeth and there's a bit of lower jaw coming through here — there. There are the teeth on the lower jaw as well. Can you see that?" I am not bored. We walk over to another technician.

"That's the eye over there," says Rubidge, pointing to a dark spot on the rock. "The nose will be there and that's the back of its skull over there, and this is the jaw joint over here and there's a bit of lower jaw coming through here.

This is a primitive flesh-eating animal from near Beaufort West." Gospel music is playing in the next room and four guys are inside it making moulds of the reborn fossils, swaying slightly to the choir as they do it, as they clone the bones.

Rubidge found his first fossil when he was five years old. After school, on weekends, on holidays, he walked in the dry Men Bethesda veld — where his father still farms — stuffing his pockets with ancient things. "From a young age I found them," he says. "I always wanted to play with this sort of stuff, and life's been good to me because it's taken me exactly here."

The professor is 56 now, balding, with thin wisps of hair that are constantly floating to his right, as if there is some exclusive weather system around his head. "I mean look at this — this is a claw of a dinosaur," he says.

We are in a different room now, one in which all the fossils that have been worked on and classified are stored. I am holding the mandible of some creature that existed before the dinosaurs. I am not bored. We leave the room and walk back through the corridors. The doors here close with a dull thunder that echoes everywhere, drowning out even the sound of the drills that are sculpting prehistory out of rocks.

Whether it just happened that way, or whether Rubidge purposefully left the best room for last, I do not know. But we are here now where the CT scanner and X-ray machine are kept. They are quietly humming and on their control panels are red digital numbers talking about what they are seeing.

There is something in the X-ray machine now — another rock, but it is surrounded by protective material so I cannot see it. "Here, look," Rubidge says. He points to an image on the computer screen. On it, flickering slightly, is the perfectly scanned image of an animal that lived long before now — a being that breathed and saw and heard, that felt hunger, thirst and fear and then died.

Then it sank into the ground, hardened, curled up in the stone like an embryo, and waited there until some palaeontologist with a spade came along in 20I3 and brought it back into the light. I am not bored. Last week it was announced that the animal inside the rock is a new species of therapod, a meat-eating dinosaur discovered in a remote region of Xinjiang, northwestern China.

It has been named by one of the centre's new members of staff, American Dr Jonah Choiniere. Rubidge looks at his watch. Hours, minutes: they must seem blurry, farcical even, to a man obsessed with billions.

He pats his gusty hair down and remembers that he has a class to teach in a few minutes. We go back to his office, which contains a large board cluttered with photographs taken on digs. Perhaps realising we have spent most of the interview talking about prehistoric bones —although this was entirely my fault — Rubidge returns to the subject of the Centre of Excellence.

"The aim of the centre is to generate new knowledge using the resources of the country where we have a major competitive advantage,” He says “now we’ve got to go ahead and make this thing work.

Rubidge crosses one leg over the other. That is when I notice his multi coloured wool socks. Concealed beneath his pants they have been there all along.

Picture by: Oliver Roberts

Source: SUNDAY TIMES