On 18 of February 2020, the Cory Library hosted the launch of Indoda Ebisithanda (The Man Who Loved Us): The Reverend James Laing among the amaXhosa 1831-1836, edited by Dr Sandy Shell, Senior Research Associate at Cory Library.

This volume was compiled from the journals of Rev James Laing, writing about his missionary life among the amaNgqika at Mkhubiso/Burnshill in the Amathole Mountains of the Eastern Cape. Cory Library Head, Dr Cornelius Thomas, chaired the event and the eminent historian of the amaXhosa, Prof. Jeffrey Peires, acted as discussant.

The book launch was accompanied by an exhibition which included all four volumes of Laing’s journals covering the years 1830-1872, volumes of minutes of the Presbytery of Kaffraria, maps positioning the mission station and surrounding Amathole area and photographs of the gravestone of his first wife, Margaret who died in 1837. The significance of Margaret’s tombstone and later, in 1872, of James Laing’s own gravestone, is that the inscriptions were written in isiXhosa. The tombstones of other missionaries in the same area were all inscribed in English, indicating the level of respect and affection accorded Laing and his wife by the amaNgqika.

Dr Shell extended her gratitude to Professor Howard Phillips, Chair of Historical Publications of South Africa (HiPSA), for his skilful editing and for the privilege of positioning this volume as the first in the third Series of the re-branded society (formerly the Van Riebeeck Society). She thanked her former colleagues in the Cory Library at Rhodes University (where the original Laing journals are held in the Library’s extensive Lovedale Collection), as well as her former colleagues in Special Collections at the University of Cape Town Libraries, the staff of Special Collections in the National Library of South Africa (Cape Town campus), and the staff of the Western Cape Archives for their support and assistance.

Dr Shell’s aim in editing Laing’s journal was to emulate, as far as possible, what historian Candy Malherbe had done to make “sensitive and imaginative use of missionary society archives in reconstructing African experiences”. She pointed out that Laing was a gentle and loving man who earned the trust of the amaNgqika, and grew particularly close to the Great Wife of the late King Ngqika, uSuthu, and Ngqika’s Right Hand son, Nkosi Maqoma. During the War of Dispossession of 1834-1835, this trust manifested significantly when Maqoma sent his wife, his children and his horses to Laing for safekeeping

James Laing was a Scotsman, not an Englishman, and Dr Shell pointed to the parallels between the tribulations suffered by the amaXhosa at the hands of the English colonial government and the sufferings the Scottish people experienced in conflict with the English. Certainly, with Laing’s insatiable interest, affection and compassion, came empathy and he deplored the aspirations, opinions and behaviour of the colonisers in Grahamstown writing that: “The feeling in this town against the black and yellow people is bad indeed. Surely people so much under the influence of prejudice are unfit for the enjoyment of that power which they seek.” His contestations with the colonial government in Grahamstown illustrate how strongly he felt about the oppression of the amaXhosa by the colonisers.

In his journals, Rev Laing describes vividly and in detail his difficulties in learning isiXhosa. He noted that his initial linguistic struggles, particularly mastering the various clicks, constituted “the greatest barrier which I see between me and the [amaXhosa]” but he was determined to persist. With his growing fluency in isiXhosa, came Laing’s gradual acculturation into the societal microcosm he shared with the amaXhosa. The full impact of the subliminal depths of this acculturation is evident from one of Laing’s obituaries in which the writers describe a delirious Laing lying on his deathbed in January 1872, fancying he could see all his friends ranged around him. He babbled volubly to these friends—in isiXhosa.

There is much linguistic value in his records as he describes the process to learning isiXhosa and correctly pronouncing the clicks within the language. Through his records it becomes evident that he earns the trust of the amaNgqika as he witnesses their customs and traditions and is given insights into the genealogical lineage of the royal houses of the amaRharhabe and the amaGcaleka through his oral interviews with significant elders in the Amathole region.

Both Dr Shell and Peires noted that diaries and journals, written in the moment, are more valuable and frank than memoirs, primarily because they are untouched by hindsight and do not rely on memory for accuracy. More than 1,500 people attended Laing’s funeral at Burnshill in 1872. Shortly thereafter, J. Masingata penned an obituary in Isigidimi samaXhosa in which he referred to Laing as indoda ibisithanda (“the man who loved us”) a further mark of the affection for Laing among the amaNgqika and the amaXhosa as a whole.

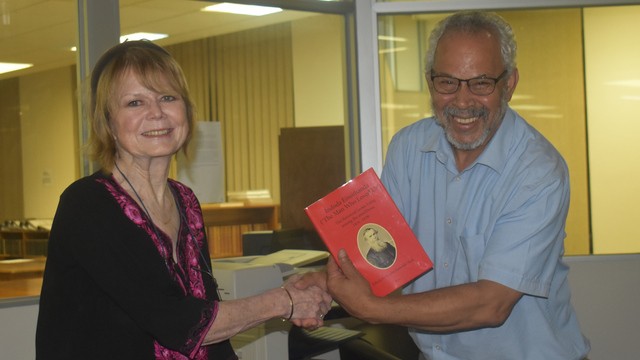

A second launch of the book took place on 20 February at the Amathole Museum, Alexandra Road, King William’s Town. The current Nkosi Ngqika, his sisters and councillors as well as representatives from the House of Traditional Leaders attended the gathering following which Dr Shell presented Nkosi Ngqika with a copy of Indoda Ebisithanda.