Standard Bank's new management structure works for the tightly knit management team — but investors are wondering whether it will work for anyone else.

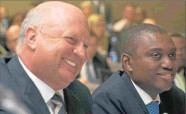

The group has controversially appointed joint-CEOs from within its own ranks to replace Jacko Maree who has retired after 13 years in charge and 32 years at the bank. Maree, 57, has been replaced by two of three deputies appointed in 2009: Ben Kruger and Sim Tshabalala.

The former, a somewhat introverted, but vastly experienced 54-year-old corporate banker with considerable global experience, joined the bank in 1985. The latter is a garrulous 45-year-old Rhodes University law graduate who signed up to Standard Bank in 2000 after cutting his teeth at the failed Real Africa Durolink. Tshabalala joined the project finance team at SCMB, where Kruger was second in charge at the time and quickly rose through the ranks.

The third deputy CEO Peter Wharton-Hood, has been appointed chief operating officer. "Banking is a club around the world," says one fund manager, "and Standard Bank is the clubbiest of them all." That close-knit culture, which has been core to the strength of Standard Bank for more than a decade, was forged in the furnace of Nedbank's ultimately failed takeover in 2000.

It brought together the most stable team in South African banking. "It proved to be a positive crisis," says Maree who replaced then incumbent Eddie Theron at the end of 1999 to stave off the Nedbank bid. He was to rebuild Standard Bank, which had been allowed to become vulnerable to the voracious acquisitive appetite of rival CEO Richard Laubscher.

It was then Finance Minister Trevor Manuel who pulled rank and blocked the bid. By then, however, the Standard Bank machine was oiled and the key players on Maree's team were in place. "It induced good behaviour among people who might not otherwise have co-operated," he says. That co-operative spirit lies at the heart of what is a unique solution to a curious problem. There was no obvious single successor to fill the considerable void left by Maree. Arguably the leadership team consists of too many potential candidates capable of leading aspects of the group but not the entire business.

At least, not yet. For outsiders the Standard Bank arrangement of joint deputy CEOs has seemed somewhat dysfunctional. But it has worked for the group with clearly demarcated responsibilities leading to a reshaping and refocusing of the bank following its failed globalisation strategy.

For Maree the story is clear cut. "I can't tell you when last I made a substantive decision about the future of the bank. We talked about issues and came up with solutions together," he says re-enforcing the point that the collaboration that will be critical for a successful partnership is already in place. Maree knew that if he held on much longer, he stood to lose senior people to more attractive opportunities and the succession issue would be no less complex.

Standard Bank had begun to haemorrhage top talent — veteran SCMB executive Kennedy Bungane, for example, saw better opportunities for himself at Absa running the Barclays Africa unit than he did at Standard Bank, where he'd developed his skills. Directors at the bank began to ask questions about who might be next to jump ship. "When I became chairman," says Fred Phaswana who replaced Derek Cooper in May 2010, "Jacko and I realised that we would both have a retirement date in 2015."

Phaswana turns 70 and Maree 60 that year and both would have reached the age at which they would be expected to step down. "We realised we would need to stagger our departures and originally Jacko said he would go in 2014 but we brought that forward because we were concerned that executives on the team were vulnerable to being poached if they saw no new opportunities for themselves to grow."

The group then faced an interesting dilemma. How to restructure a strong team that was beginning to get the business effectively re-aligned, particularly in terms of its Africa strategy. The executive team had completed its 2016 plan by the middle of last year and was ready to execute it. Maree and Phaswana came to the conclusion that the team was probably best left to do precisely that — take the new strategy and run with it.

It seemed that March 2013 would be an opportune time for Maree to take his leave, but were they missing a trick? Was it necessary to have a single overarching CEO? The board consulted HR, which looked in the domestic banking market for a suitable successor. HR also considered whether it would be appropriate to consider global candidates and quickly came to the conclusion that an outside appointee simply would not fit the Standard Bank culture and bringing in a foreigner would send the wrong signal through the bank.

So it was back to the thorny issue of choosing a successor from a limited internal pool without unsettling a team the board wanted retained. Did Maree overstay his welcome? No, he insists — but he is cognisant of the fact that by clinging to the mantle too long, he was at risk of losing top talent to voracious predators all of whom would be tempted to pay top dollar for the skills of a tightly knit management team...

The race for the top spot was wide open when the December holidays started. It was early in the new year when discussions began in earnest with a small selected group of senior executives on an individual basis. It soon emerged that the senior leadership of the bank was keen to avoid unnecessary controversy and certainly wanted none of the indignity that surrounded the 2007 appointment of Barloworld chairman Dumisa Ntsebeza and his deputy Trevor Munday.

Munday was put into the newly created post, in a support role to the newly elected Ntsebeza, in a move the Public Investment Corporation described as: "racist, condescending and patronising". Despite Ntsebeza objecting to the criticism of his appointment, Munday stepped down and left the group. Standard Bank wanted to avoid an unseemly political mess that would compromise the integrity of its most senior executives. Kruger and Tshabalala emerged as clear frontrunners, although other key executives were consulted at various points through the process.

The bank is wary of losing the talents of retail head Peter Schlebusch and SCMB head David Munro and there was a risk of offending co-deputy Peter Wharton-Hood, who'd built a niche in technology and systems. He appears to have settled for the pivotal role of chief operating officer.

Kruger knew he would face difficult questions about the future prospects of talented black executives if he were supplanted over Tshabalala. Tshabalala knew that he would face similar issues among talented white colleagues who might perceive there to be a glass ceiling and might be tempted to new jobs if they thought they might be overlooked for future opportunities. There is also a considerable amount of water under the bridge.

Kruger has mentored Tshabalala, who refers to him as "Pliny the Elder" (a first-century Roman intellectual), in deference to his experience and overall banking wisdom. It's unclear who first suggested the dual CEO role. Both candidates agreed it was an elegant solution to an otherwise intractable problem that would leave the loser in any leadership contest with little choice but to leave the bank.

So it was in January that Tshabalala and Kruger set about the task of how they would separate their responsibilities in a way that would play to their respective strengths, that would placate regulators and would convince the board that there was no risk of a divide-and-rule mentality creeping into the business.

Within a month they reported back to Maree and Phaswana that they had sorted it out. Tshabalala remains CEO of Standard Bank South Africa and takes charge of the group's banking businesses outside South Africa.

JACKO MAREE'S CEO career was a baptism of fire that saw him pit his still-green corporate wits against those of the more experienced Richard Laubscher. Had Nedbank succeeded in taking over Standard Bank, his career would likely have taken a very different path. Standard Bank was trading around 2100c when Maree took over and last week traded around 11800c.

The dividend is up nearly seven times and the group's value rose more than sixfold in the ensuing decade. After seeing off Nedbank, Maree and his hand-picked band of executives restored the dignity and reputation of the group, entrenching it in South Africa the group's banking businesses outside South Africa, on the African continent, including oversight of the group's investment in Liberty Holdings run by Bruce Hemphill.

Finance Director Simon Ridley reports to him. Kruger, in turn, remains in charge of personal and business banking as well as corporate and investment banking while being responsible for the group risk function. Wharton-Hood reports to him. Members of staff at Standard Bank are perplexed with the changing of the old order as reporting lines and budgets are restructured to reflect the new command and control structure which time will show is either a great accomplishment of mutual co-operation or a damning indictment of an inadequate group succession process.

Time will tell. Brand Pretorius, who is head of the Absa nominations committee and author of a personal memoir and book on leadership In the Driving Seat pays tribute to the strength and depth of the management team that competes aggressively with his bank across the African continent but says the solution is far from ideal. "Much will depend on the role of the chairman and his ability to ensure that egos are kept in check!'

By appointing two chief executives, Standard Bank may have made a rod for its own back. Has it made the appointments because as it suggests, there is other international evidence pointing to its efficacy — particularly Deutsche Bank, which has two heads. But, caution banking sector experts, if it is an admission that the bank is too big and too complex for one individual to manage, then it could count against the group in future as regulators around the world apply pressure on financial institutions that are regarded as too big to fail and thus pose significant systemic risk to financial systems.

South Africa's banking regulators have approved the new structure, which stands to be tested should there ever be issues around governance and decision making at the highest level. Until then, Tshabalala and Kruger have opted to work together for the greater benefit of the group as the country's premier retail bank with strong earnings from both the branch network and from its solid corporate and investment banking operations.

He added branches across the African continent but also looked further afield. He concedes that there was probably an opportunity cost to expanding the way they did into Turkey, Argentina and Russia but stresses that once it was clear that the market had changed, they took the critical decision to exit markets they'd entered, at a profit in the case of Latin America and the group has also succeeded in getting its investment back from Moscow.

He regards the decision to sell 20% to China's ICBC as a career highlight that will continue to define the group in the future. Did he overstay his welcome? Despite being ready to move on two years ago but electing instead to return the group to an even keel before leaving, he doesn't think so. Does he now report to Kruger and/or Tshabalala?

The response is a swift and emphatic: "No," he will report to the chairman as he stays on as "senior banker" in a US tradition for outgoing CEOs who harbour no desire to embark on a long and illustrious career as a non-executive director.

The group's banking businesses outside South Africa, on the African continent, including oversight of the group's investment in Liberty Holdings run by Bruce Hemphill. Finance Director Simon Ridley reports to him. Kruger, in turn, remains in charge of personal and business banking as well as corporate and investment banking while being responsible for the group risk function.

Wharton-Hood reports to him. Members of staff at Standard Bank are perplexed with the changing of the old order as reporting lines and budgets are restructured to reflect the new command and control structure which time will show is either a great accomplishment of mutual co-operation or a damning indictment of an inadequate group succession process. Time will tell.

Brand Pretorius, who is head of the Absa nominations committee and author of a personal memoir and book on leadership In the Driving Seat pays tribute to the strength and depth of the management team that competes aggressively with his bank across the African continent but says the solution is far from ideal. "Much will depend on the role of the chairman and his ability to ensure that egos are kept in check."

He concedes that there was probably an opportunity cost to expanding the way they did into Turkey, Argentina and Russia but stresses that once it was clear that the market had changed, they took the critical decision to exit markets they'd entered, at a profit in the case of Latin America and the group has also succeeded in getting its investment back from Moscow.

He regards the decision to sell 20% to China's ICBC as a career high- light that will continue to define the group in the future. Did he overstay his welcome? Despite being ready to move on two years ago but electing instead to return the group to an even keel before leaving, he doesn't think so. Does he now report to Kruger and/or Tshabalala?

The response is a swift and emphatic: "No," he will report to the chairman as he stays on as "senior banker" in a US tradition for outgoing CEOs who harbour no desire to embark on a long and illustrious career as a non-executive director.

Bruce Whitfield brucew@finweek.co.za

Gallo lmages

Source: FinWeek