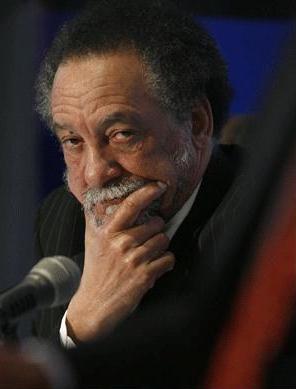

The death of Rhodes University chancellor Jakes Gerwel will leave a big void in many people’s lives.

One of the first messages of condolences following the death of Rhodes University chancellor Prof Jakes Gerwel came from a retired academic who said he was “a good and great man. He will be hard to replace”.

The chairperson of Rhodes’ UK Trust, Geoffrey de Jager, wrote: “What sad and devastating news. A great man who often gave me wise counsel, his death will leave a big void in many people’s lives.”

I first met Jakes Gerwel in 1987 at the London apartment of former deputy minister of foreign affairs, Aziz Pahad.

This was soon after Gerwel became vice-chancellor of the University of the Western Cape (UWC).

I was excited by his commitment to make UWC the “intellectual home of the democratic left,” and was thrilled when he invited me to consider joining UWC when I returned to South Africa.

Joining UWC in 1989 was the smartest thing I have done in my life.

Many black intellectuals and scholars like myself owe our achievements and positions to Gerwel’s bold and inspired leadership and the exciting intellectual environment that he cultivated at UWC.

And so it was exciting to be formally linked with him again when I became vice-chancellor at Rhodes in 2006.

He will be fondly remembered and greatly missed as chancellor of Rhodes University.

A humble, gentle man of great integrity with a lively mind and intellect, he was always a source of good judgement and wise counsel.

He will be warmly remembered for the grace and dignity with which he officiated at the university’s graduation ceremonies and capped thousands of graduating students.

Born on January 18 1946 in Somerset East in the rural Eastern Cape, Professor Gert Johannes Gerwel was a product of historically disadvantaged schools in the Eastern Cape.

Like most black South Africans of rural backgrounds, he had to triumph over the apartheid and Verwoerdian dictum that there was no place for blacks beyond being hewers of wood and drawers of water.

In a country deeply challenged to improve schooling and realise the potential and talents of all our youth, his example of a rural boy who achieved remarkable success under adverse conditions must serve as a source of inspiration for young people who today struggle with the burden of dismal educational opportunities.

Gerwel was an exceptional, courageous, gifted and pioneering South African intellectual, scholar, leader and citizen. He had a profound commitment to creating a just and humane society.

Through a long and distinguished association with the higher education sector, as an academic, dean, vice-chancellor, chairperson of the Committee of University Principals in the early 1990s, chancellor, and chairperson of the Mandela Rhodes Foundation, Gerwel was an outstanding champion of higher education.

As chancellor, he challenged Rhodes to become socially conscious and think critically and imaginatively about access, equity and transformation, and about its role in socioeconomic development issues in South Africa, especially in the Eastern Cape.

On accepting an honorary doctorate from Rhodes, Gerwel said: “Universities are both central agents for change and steady beacons of continuity and tradition”.

He was a strong advocate of Rhodes University pursuing, in a principled manner, equity with quality and quality with equity. He took pride in the university’s academic achievements and performance in research and teaching and its increasing involvement in community engagement.

The Jakes Gerwel Rhodes University Scholarship Fund is testimony to his own life of achievement and supports Eastern Cape students from socially disadvantaged backgrounds to attend Rhodes University and graduate from one of South Africa’s leading tertiary institutions.

Gerwel was not only a significant figure in higher education, but also an important beacon in the economic, social and political life of South Africa more generally.

There were many pioneering firsts.

On June 5 1987 he became the first radical vice-chancellor, not only of UWC but of any South African university.

He led the rejection of the apartheid principles on which UWC had been established. Noting that the “Afrikaans universities stand firmly within the operative context of Afrikaner nationalism”, and that “the English-language universities operate within the contexts of anglophile liberalism”, he observed that there was no university linked to “those people and institutions working for a fundamental transformation of the old settler-colonial order”.

In this context, he declared that UWC faced “the historical imperative to respond to the democratic left, to be an intellectual home for the left”. This meant that UWC had to “develop a critical alignment with the democratic movement” and had to “educate towards and for a changed society”.

Gerwel stated that he could not “in conscience, in truth, educate or lead education towards the reproduction and maintenance of a social order which is undemocratic, discriminatory, exploitative and repressive”.

Gerwel was too good and thoughtful an intellectual to reduce a university to a political institution.

President Mandela has noted: “The nation drew inspiration from (UWC’s) defiant transformation of itself from an apartheid ethnic institution into a proud national asset: from its concrete and manifest concern for the poor, for women and rural communities, and from its readiness to grapple with the kinds of problems that a free and democratic South Africa was to deal with later”.

Archbishop Desmond Tutu recalled Gerwel saying, especially at a time when it was unpopular: “We are on the side of the downtrodden, we are going to work for the upliftment of our people.”

Under Gerwel, UWC rejected apartheid, and committed itself to non-racialism, non-sexism and social justice and “the development of the Third World communities in South Africa”.

Access was opened to all South Africans and UWC began to ditch its previous baggage as a “coloured” and “bush” university.

Intellectual debate flourished and UWC became an exciting space for socially committed and engaged scholarship.

Gerwel took knowledge and intellectual work seriously.

As he was wont to point out to the more action-oriented: “Good intellectual work entails hard work of a special type. It is as difficult, if not more difficult, than organising door-to-door work, street committees and mass rallies.”

He did not, however, eschew action.

He stood shoulder-to-shoulder with protesters in Cape Town during the defiance campaign marches of the late 1980s.

And during protests at UWC that often spilled onto the streets, he shielded students and academics confronted by riot police armed with rubber bullets and tear gas.

Gerwel’s Literatuur en Apartheid, published in 1983, remains a key text in the Afrikaans and southern African literature discourse. He also published various monographs, articles, essays and papers on literary, educational and sociopolitical issues.

There was educational innovation that was years ahead of any other university.

One area of profound work was in academic development programmes, which sought to provide “epistemological access” and real equality of opportunity for the poor.

Gerwel helped to significantly advance gender equality at UWC. Compared with men, women at UWC suffered many disabilities related to salaries, benefits, pensions, leave and the like.

While the efforts of women at UWC were decisive, Gerwel’s support as the vice-chancellor was critical in creating a more gender-equal institution.

The early 1990s saw UWC become a key site for policy research in support of an equitable and democratic South Africa.

Gerwel brought those of us working in the arena of higher education policy development into conversation with others working on constitutional, economic, trade, health and other policy issues.

Many of those involved in such policy work have become Cabinet ministers and leaders of institutions post-1994.

Another first was when Madiba recruited Gerwel to become democratic South Africa’s first director-general and Cabinet secretary in the office of the president.

Later, he chaired the Nelson Mandela Foundation and the Mandela Rhodes Foundation, which awards postgraduate scholarships to talented students.

The numerous honorary doctorates awarded to Gerwel and his extensive leadership roles in civil society, business and sports organisations are all testimony to the respect he enjoyed in all spheres.

He can rest content in the knowledge that he lived his life as advocated by an outstanding revolutionary, Nikolai Ostrovsky: man’s dearest possession is life.

It is given to him but once, and he must live it so as to feel no torturing regrets for wasted years, never know the burning shame of a mean and petty past; so live that, dying he might say: all my life, all my strength were given to the finest cause in all the world – the fight for the liberation of humankind.

Xolani Nyali, a former Rhodes SRC president who came into contact with Gerwel, wrote to me: “He ran his race, it is now complete. Others must take over from where he left off.” Indeed!

Hamba Kahle, bold, humble and gentle man, leader and mentor of great integrity, intellect and dry and understated humour. You will be dearly missed.

picture credit: Felix Dlangamandla Foto 24

- Saleem Badat is vice-chancellor of Rhodes University. This article was published on http://www.citypress.co.za.