(Image from http://www.brothersforlife.org)

On Sunday, the 15th of June, Father’s Day, my sister and I had breakfast at Spur on our way back to Grahamstown from Cape Town where we had spent the weekend. While eating, we heard the manager doing his rounds, making sure that people were enjoying their meal, and generally having a good time. Enjoying our own meal and talking in between mouthfuls, snippets of this ‘small talk’ wafted over to us. Included in his ‘small talk’ was some commentary on ‘real’ versus ‘fake’ fathers, made relevant (of course) by the fact that it was Father’s Day. As our eavesdropping revealed, ‘fake’ fathers are men who have children and run off, leaving their (female) partner to raise the children. ‘Real’ fathers were those seen at Spur with their families in the role of provider (assuming that they would be taking care of the bill) as well as loving, involved/present father who spends quality time with his children: the ‘new man’.

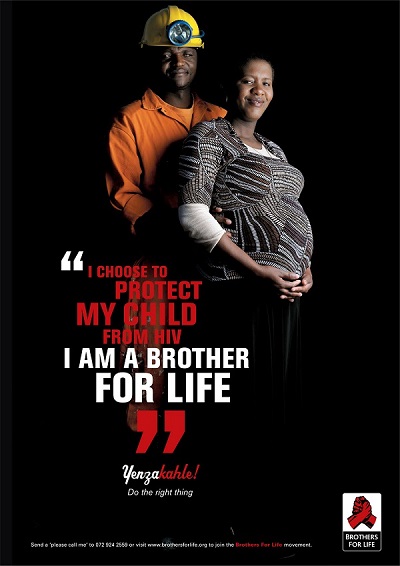

In addition to the spaces in which everyday conversation takes place, this ‘new man’ discourse in South Africa has also been taken up in ‘official’ and public spaces such as government-directed campaigns to stop violence against women and children and eliminate gender inequality and its associated consequences (e.g. the gendered lines along which the HIV epidemic has spread). Recall, for example, the Brothers for Life slogan ‘Real men don’t rape’. Citizen-directed protests/campaigns have also made use of this discursive resource (recall, too, that the Silent Protest held annually at Rhodes University has also made use of the slogan). This turn to a ‘new man’ discourse may partly be due to the recognition that dominant ways of doing masculinity, which include the valorisation and endorsement of male authority and control, particularly the use of violence and aggression to achieve it (Sideris, 2005), contribute to and perpetuate violence against women and children.

Despite this recognition and despite the taking up of this discourse, violence against women and children is still a significant problem in South Africa. Indeed, this is the case in most parts of the world. In Chibok, Nigeria, over 200 school girls were kidnapped about 60 days ago by a group who present themselves as militantly against western education. Recently in another part of the world, two girls aged 12 and 14 (cousins) were raped, murdered and then hanged in a tree in Uttar Pradesh, India.

These acts of violence may be seen as part of a larger, dominant discourse that views women as subordinate to men and men as having both the authority and the responsibility to control women’s movement and sexuality and to use violence in the process. This discourse also constructs women (and young girls) as objects to be used as pawns in a struggle for power. Seen from this perspective, these actions may be seen as one of many widely accepted ways of doing masculinity. If so, the solution, then, becomes finding ways of doing masculinity that go against such dominant discourses.

However, as Macleod (2007) notes in her paper on phallocentrism in masculinities studies in South Africa, such a project may be a huge undertaking, one that might be doomed to fail. In the fragmentation of masculinities, some ways of doing masculinity are pitted against others, for example: alternative/ hegemonic masculinities, ‘real’/’fake’ masculinities etc. The result, as Macleod (2007) argues and Sideris (2005) suggests in her paper, is that ‘masculinity’ is never undone. This ‘new man’ masculinity, while finds new ways of doing masculinity, retains much of hegemonic masculinities which are problematic in and of themselves. Hence, according to the Spur Manager, while ‘real’ men do not leave child-rearing responsibilities to their female partners, they still occupy the role of provider and head of the family. Similarly, in campaigns such as Brothers For Life, the ‘new man’ is admonished for the use of violence against women and children but is instructed to protect and safe guard his woman and his children, much like he would with his property. That new ways of doing masculinity do not undo (hegemonic) masculinity could perhaps explain why violence against women and children, and other forms of oppression, still continue despite the taking up of the ‘new man’ discourse.

By Jabulile Mavuso.

Links:

References:

- Sideris, T. (2005). “You have to change and you don't know how!”: Contesting what it means to be a man in a rural area of South Africa. African Studies, 63(1), 29-49.

- Macleod, C. (2007). The risk of phallocentrism in masculinities studies: How a revision of the concept of patriarchy may help. PINS, 35, 4-14.