In the Students’ Union Foyer, at the base of the University of Cape Town’s Jagger Library, hang a series of paintings by the South African artist Richard Baholo. These form part of a permanent exhibition that commemorates the university’s resistance to the key instrument of racial segregation in the apartheid era, the 1959 Extension of University Education Act, and celebrates the final stage of its repeal in 1993.

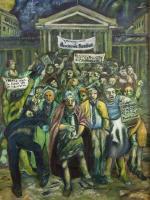

One particular painting depicts a demonstration against [former president] FW De Klerk’s regulations that took place at the University of Cape Town, or UCT, on 28 October 1987.

For me, the painting captures a certain dimension of academic freedom, one that was powerful enough to be registered by the new Constitution, but has been undermined since then in most policy, discussion and debate.

In the painting, with a sense of irresistible forward momentum, a crowd of academics, workers and students flows down the steps from UCT’s Jameson Hall. The forces of apartheid law and order – here figured as a single policeman in blue on the bottom left of the painting – are pushed casually aside by the crowd.

They carry placards which reiterate the key educational slogans of the day – ‘Forward to a people’s education’, ‘Education is a right not a privilege’, ‘VIVA NUSAS VIVA SANSCO AMANDLA’ – long live student activist groups – while the specific occasion of the demonstration is made evident by those reading ‘PHANSI [down] with De Klerk’s bills on education’ and ‘No subsidy cuts for UCT’.

What interests me most is the central organising banner for the demonstration, and from which the demonstration seems to flow: how it gathers everyone together under the slogan of academic freedom – or more specifically, ‘Stop de Klerk assault on academic freedom’.

What this painting evidences, I would suggest, is that at this moment in the social imaginary, academic freedom is seen as a positive social force and as an essential component of the democracy to come.

My book, Academic Freedom in a Democratic South Africa (Wits University Press 2013), argues that we should insist on remembering this once powerful sense of academic freedom as a positive social force at a moment when policy and politics together are determined that we forget it.

Occasioned writing

In this attempt, the book’s various essays and interviews are best read as examples of a particular kind of occasional writing that we might call occasioned writing.

While occasional writing refers largely to a specific literary genre – that of the writings produced by poets laureate to mark and celebrate specific national occasions – occasioned writing does, or seeks to do, something else.

Occasioned writing in the sense I put forward here is academic writing addressed to a public moment in a deliberately reflexive manner, and its central task is to try and disturb the easy flow and circulation of received ideas.

It seeks, as Edward Said put it, to “break the hold on us of the short, headline sound-bite format and try to induce instead a longer, more deliberate process of reflection, research, and inquiring argument that really looks at the case in point”.

In occasioned writing, the academic writer moves cautiously beyond the usual scope of disciplinary specialisation, and steps outside the charmed circle of a purely professional address to fellow scholars, and seeks to find or address a more open and undefined public. As such, they necessarily run the many risks inherent in that form.

At the same time – and as is apparent in the concrete arguments engaged in each chapter – the wager of the book as a whole is that specialist literatures themselves tend to embody forms of professional consensus that can have their own blind spots and biases, and that these are perhaps more easily registered by an outsider’s eye.

Assault on academic freedom

Academic Freedom in a Democratic South Africa is motivated in large part by a dismaying sense – at least with regard to the difficult and contested relations between the university and the state – that the wheel has come full circle, and that this is so in ways that were certainly never anticipated when its first chapter was written.

For the first chapter – “The Warrior Scholar Versus the Children of Mao” – was prompted by the threats to academic freedom embodied in the ‘de Klerk regulations’ of 19 October 1987.

Current Minister of Higher Education and Training Dr Blade Nzimande’s Higher Education and Training Laws Amendment Act of 2012 appears to threaten an unexpectedly similar assault on the autonomy and academic freedom of South African universities.

The sense of these disturbing continuities has already surfaced in public responses to the new Higher Education and Training Laws Amendment Act.

Barney Pityana, former vice-chancellor of the distance University of South Africa, argues that “rather as in apartheid style legislating”, the Nzimande regulations “give the minister open-ended and ill-defined powers to intervene in higher education institutions well beyond the powers already available to him”.

Professor Ihron Rensburg, vice-chancellor of the University of Johannesburg, emphasises that the new legislation – though at the moment of writing, still to be signed into law by President Jacob Zuma – “undermines the careful balance struck between university autonomy and public accountability crafted by the Constitution and the initial Higher Education Act”.

The new act not only gives “one individual enormous power over the higher education system”, he warns, but “also confuses the ‘public’ with the ‘state’”.

Similarly, and in line with Rensburg’s analysis of the anti-democratic authoritarianism at work in the new legislation, is the simple fact that it was developed without following any of the usual processes of consultation with stakeholders and interested parties established in higher education to encourage democratic participation and accountability since 1994.

Neither the statutory Council on Higher Education, which exists precisely to advise the minister on higher education matters, nor HESA – Higher Education South Africa – the body that represents all 23 vice-chancellors at South African universities, were consulted prior to the promulgation of the new act.

“Under normal circumstances,” notes HESA chair Professor Ahmed Bawa, vice-chancellor of Durban University of Technology, “the minister would have consulted us on his intentions to introduce new amendments to the act and would have given a context for the new amendments and the inadequacies they seek to address in the current legislative framework”.

The Council on Higher Education notes: “New Clause 8 – 49A (1) is even more broad and open-ended and provides the minister with the power to intervene and to issue directives on a range of matters and the power to appoint an administrator if an institution does not comply.

“The nature of the directives that the minister can issue and the steps that institutions would be expected to take in response are not defined, nor are there any limits placed on ministerial action.”

These and other responses suggest that the new Nzimande regulations, like de Klerk’s before them, may similarly be found to stand ultra vires: that is, above and beyond the scope of the administrative power envisaged for the minister by the Constitution and therefore null and void.

That will have to wait for the decision of the Constitutional Court, if the matter goes that far, as HESA fears it will.

Debates far from over

In any case, whatever the outcome of this potential conflict in the Constitutional Court, the intended new legislation draws attention to the simple fact that debates around institutional autonomy and academic freedom – and indeed the very definition of the university and its purposes in the contemporary world – are far from over.

Academic Freedom in a Democratic South Africa maintains that in these current debates around the social functions of the university, it is essential not to lose sight of or marginalise the teaching of the humanities.

In retrospect – and not surprisingly – the reader will find that the essays here all necessarily tend to embody much of the case they end up arguing for.

It is the book’s central and defining idea that the core skills of humanist education – often referred to as the skills of a ‘critical literacy’ – have much to contribute to the public good in ways which are being denied, or simply made invisible by the terms currently dominating higher education policy.

* University of Cape Town fellow Professor John Higgins’ new book, Academic Freedom in a Democratic South Africa was recently published by Wits University Press.

Source: John Higgins 29 November 2013 Issue No:298

http://www.universityworldnews.com/article.php?story=20131127205648328