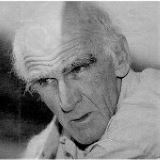

Today I got to spend the afternoon hanging out with a bunch of bright, talented kids from Southern Cross School, discussing 1 of my favourite human beings and 1 of South Africa’s finest poets, Don Maclennan.

Don died in 2009. He was my English tutor at Rhodes University, and so much more. His lessons and his poetry have been constant companions and it was a delight to see the grade 10 and 11 students meet Don, through his words.

One of my 1st ever journalism profile writing assignments was on Don. Written with all the wisdom of my 18-year-old self, rereading it took me right back into his classes. Inexplicably, I used to cry in his tutorials. I had no idea why. I’m not really the crying type.

Inexplicably, I used to cry in his tutorials. I had no idea why. I’m not really the crying type.

It was a combination of his voice, his presence and something more. One day after class, he asked me what on earth was going on. I couldn’t explain and he invited me to tea. Visiting his house and talking with him are some of my most treasured varsity memories. Many knew him much longer and much, much better than I did. But what I knew, I loved. And his words speak on to me, in the most personal way.

Here is the profile I wrote more than 10 years ago.

Don is tall. He is old. He is going to die. He is an old poet who is going to die. He makes me cry. He also farts, burps and shits, or so he assures me. For some reason this makes me want to cry more than ever, but I’m also smiling because listening to this man is like discovering the taste of something you can only smell; something dry and flinty, flavoured with citrus and time. A honeyed finish and something more, gone before you can grasp it.

When someone has such a history with words, using yours to try to describe him is an intimidating task. You note what he says or how he looks. You read his poems. You listen to the beauty of his voice as it grates, cuts, chews and mulls over words, his own and others.

He is reading Gerard Manley Hopkins. The words of “The Windhover” soar, turn and “fall, gall themselves, and gash gold-vermilion”.

"What is poetry?” he asks his students. He sounds interested. His tutorial group is moved, puzzled, curious and earnest. They think he knows something that they don’t. “It’s simply that they are wrong,” he mumbles to me while their discussion continues. “I’m a genuine fraud.”

Later he asks “was I born?” when I want to know where. I confirm that he was. As it turns out, it happened in London on 9 December, the same date as John Milton and Joseph Stalin except in 1929. He grins and I think he likes being caught between this metaphorical rock and hard place. He likes it literally too, being an avid climber and fond of archaeology. He once travelled through the Free State in a baby Austin learning to recognise stone tools. He found the large Stone Age hand axe on his desk in Tanzania 51 years ago. Its symmetry still pleases him.

After being born, Don Maclennan grew up, and has published numerous plays, volumes of poetry and an impressive collection of literary criticism (this is a lovely tribute to Athol Fugard, another great South African writer). He has burnt 9 novels. He came to South Africa in 1938, went to St Johns College in Johannesburg. Then he went to Wits. Two years later he left in a 1936 Chevy, and didn’t come back. He climbed the Mountains of the Moon and 1 day arrived in the Seychelles, on a North Sea fishing trawler. “How does one arrange to be stranded there for two months?” I ask him. He smiles, his bushy eyebrows slightly arched.

“Eventually, a friend found me hiding away in England, wondering what to do with my life,” he remembers. They left for Edinburgh; he got a degree in philosophy, met his wife and moved to America. In 1966 he got a job in the English Department of Rhodes University with Guy Butler. He helped start a black theatre group, and acted in a play he wrote: The Third Degree.

It emerges that he has just got back from a book launch in Cape Town. “I didn’t stay around long enough for it to flop, and the best part were the Russians, who made a lot of noise,” he says evasively when I ask about the event. “Let’s have some tea.” I still don’t know if it was his book being launched.

I struggle on with my questions, suspecting that he has enough for both of us. Maybe some of the questions are actually the answers. I walk down the stairs. He follows and we pause in the foyer. He limps, but I don’t know why. Making tea, he mentions an author I tell him I have never read. “Maybe you need a more comfortable chair,” he speculates.

Tea in hand, we go back to his office. He talks about a wonderful family and his love of Mozart. The painting on the wall is his, a Karoo landscape with intimations of immortality in every line. I know he plays the violin and holidays in Crete. He points to a picture of himself as a four-year-old in a boat on Loch Ness. “I knew the water was cold and there was a monster in there and I couldn’t swim,” he says, blue eyes burning.

“I seldom have two thoughts to rub together,” he confesses when I finally ask him about writing poetry. He’s rubbing something together though. Figs and sunshine? Dante and approaching death? Perhaps just the simple fact of being in the world. Alive to it. Open to it. But only for a while.

I will never forget Don’s lessons; “that poetry enacts its meaning”, and to quote Sydney Clouts as Don often did, “Poetry is death cast out.” I will never forget Don’s generosity – with his intellect, words, ideas and time. I will never forget these lines from Solstice;

I cannot tell you of the universe

that talks to me

like an inner spring –

a sunrise that I helped achieve itself,

a sea that darkens and darkens

into Homer’s wine.

In a paper on Guy Butler, Don said that “the best poems are those with a deeply meditative force. Perhaps this is so because poetry is a serious and central human undertaking. Poets are not found in the Pentagon, nor are they asked to speak in parliament. Yet somehow poets do remain hidden legislators, because they listen in the stillness beyond words to the deepest source of all.”

Dan Wylie, who had a very special relationship with Don (and incidentally also taught me), said the life and nature of Don Maclennan can be summed up in the words printed on the shirt he was wearing when he died: “I have nothing, I want nothing, I am free.”

There are some great tributes to him on line on Kagablog (including some of his poetry set to music). I loved reading every single one. I wish I’d been at this colloquium. I hope there will be another 1 sometime. Here, 1 year after he died, friends share particular memories.

Under Compassberg II Scatter my ashes on the summit I so loved Let the Dolerite have what’s left of me. When the wind blows from the north the scent of agathosma will enfold me.

Watching him read Last Wish, predictably made me cry again.

Article by Dianne Tipping-Woods

Article Source SouthAfrica.net