CHIEF Albert Luthuli is a Nobel Prize winner who receives less attention that he deserves, for his life has important lessons.

From his earliest days in the ANC Luthuli spoke of the “gospel of service”, embracing a social gospel, a Christianity that understood serving the Creator as signifying serving the cause of freedom, the equality of all God’s creatures, without thought of reward.

He told the Natal ANC in 1949: “We cannot say that Africans are accepting fast enough the gospel of service and sacrifice for the general and larger good without expecting personal and at that immediate reward. They have not accepted fully the basic truth enshrined in the saying ‘no cross no crown’.”

Luthuli had the opportunity to enrich himself. He was an elected chief, but one who had been granted criminal jurisdiction. He could have augmented his meagre salary through exacting fines, legally or semi-legally, but he never accepted fines.

Long before he became chief, villagers had repeatedly asked him to make himself available. He was reluctant to respond to the “call”, because he was the breadwinner and a chief earned much less than a teacher at Adams College, where he was working.

But he and his wife, Nokukhanya, MaBhengu, changed their minds and he relates this to how he understood his faith. He had learnt that “the Christian faith was not a private affair without relevance to society. I had to do something about being a Christian, and that this something must identify me with my neighbour, not dissociate me from him…”.

This raises an important question of ethics; how one moves from understanding that something is right or wrong, at an intellectual level, to deciding to take responsibility and acting on one’s beliefs.

This means unifying one’s rationality and passion for the cause in which one believes, a form of spirituality.

One can be very learned in the Bible, marxism or any other doctrine but not be able to join that with the willpower required to act on it.

There are many people who undertook commitments in the struggle but faltered when they encountered hardship, because they had not prepared themselves for what it meant to face prison or other repression.

Both Luthuli and Nelson Mandela prepared themselves to act with courage. In his Nobel lecture in 1961 Luthuli said what was needed then was “the courage that rises with danger”.

Luthuli had already done this in rejecting the government’s ultimatum to choose between the ANC and being a chief in 1952: “What the future has in store for me I do not know. It might be ridicule, imprisonment, a concentration camp, flogging, banishment and even death. I only pray to the Almighty to strengthen my resolve so that none of these grim possibilities may deter me from striving, for the sake of the good name of our beloved country… to make it a true democracy…

“It is inevitable that in working for freedom some individuals and some families have to take the lead and suffer: The road to freedom is via the cross.”

Luthuli is associated with peace but he reluctantly accepted the turn to armed struggle. Nevertheless, for him, non-violence was an unconditional good. We need to understand that non-violence is a precondition for relationships based on respect between members of our society.

Departures from that principle can only be conditional and limited.

Umkhonto we Sizwe was justified, I believe, as a conditional exception from the norm, because of apartheid’s armed attacks on the people of South Africa.

Once that condition was removed, with the inauguration of a democratic order, resorting to arms was no longer justified. We need to instil this understanding in all members of our society.

Finally, in a society, which is troubled by violent masculinities, imagery of rough tough men and a history of settling problems by force and not reasoning, Luthuli embodies an alternative model of manhood.

Like Mandela, Luthuli was both strong and also gentle, as seen amongst other places, in his home.

He used to read his speeches to Nokukhanya. His daughter Dr Albertinah Luthuli records that when uMama listened and had made her contribution, uBaba (Father) felt strengthened to go and deliver it.

In other words, his daughters could observe that despite Luthuli being a national leader, he was vulnerable and needed to draw strength from his wife. He did not hide this from them. He was not ashamed to be both strong and vulnerable, as all of us are.

They also report on his tenderness, how he would cover them when a blanket fell off or gently return a child who was sleep-walking back to her bed.

This is the type of masculine leadership we need to build: men who are not afraid to show gentleness or vulnerability, men who are prepared to sacrifice, who do not boast of what they will do but prepare themselves to do what is right, without thought of reward.

By Raymond Suttner

Source: Daily Dispatch

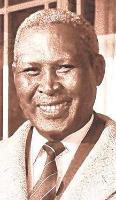

Caption: Strong and gentle: Albert Luthuli

Professor Raymond Suttner is attached to Rhodes University and Unisa, and is an analyst and speaker on current political and historical questions. He is a former political prisoner and was in the leadership of the ANC-led alliance.

This article first appeared on Creamer Media’s polity.org.za.