IF THE social justice agenda here depends on inflating the popular support and the commitment to equality of a loud group of racial nationalists, it is in more trouble than we thought.

The nationalists are the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF), whose 6.35 percent of the vote has been hailed by the media, commentators and voices on the left. If we look at the numbers, it is hard to see why the EFF should deserve this hero-worship. If we look beyond them, we will find the reaction to Julius Malema's party more interesting than the EFF itself.

The EFF received 14 percentage points fewer votes than the Congress of the People's 7.42 percent in 2009. It won almost 150 000 votes fewer than Cope did then even though more people voted this time.

Then, the mainstream debate, which repeatedly hypes up ANC breakaways, found Cope's performance disappointing. Now, a poorer performance has been hailed as a triumph.

Since the election, the EFF and its supporters among the commentariat have reacted indignantly to the Cope analogy They claim Cope had resources which the EFF lacked — one of its leaders was a cabinet minister, it took with it ANC branches and had lots of money.

But the EFF had, if anything, more reason than Cope to do well. Cope was formed only months before the election. It chose as its presidential candidate Bishop Mvume Dandala, who had never been an ANC politician — since it was appealing to ANC voters, this was a huge blunder. The EFF had much more time to prepare — its "commander-in-chief", Malema, may not have been a minister, but is better known than Cope's Mosiuoa Lekota.

EFF enjoyed almost unlimited media coverage, all of which portrayed it as it wanted to be seen, as a radical party with a mass following among the poor. While social media still reach probably no more than one in 10 South Africans, Twitter and Facebook enabled it to reach connected young middle-class voters, an asset Cope did not enjoy Like Cope, EFF could rely on existing ANC structures and so had readymade networks it could use to reach voters.

All this means that the EFF should have done at least as well as Cope. That it did not, shows that its popularity has been greatly exaggerated.

The EFF did not present itself, nor did commentators and reporters present it, as just another party seeking a toehold in Parliament; it presented itself, and was portrayed, as the voice of all who felt betrayed by two decades of democracy.

Its repeated claims that it would win a majority were not simply routine boasts. It portrayed itself as the voice of the poor and dispossessed. Since they are a majority a party which speaks for them would be assured victory Journalists and commentators repeatedly portrayed the EFF as the nemesis of the social pact of 1994, the voice of all whose material needs had not been met by the constitutional order.

That this history-changing movement turns out to enjoy the support of only one in 16 voters — if we take into account how many people register, one in 20 voting-age citizens — shows how great a delusion the notion of EFF as a history-changing mass movement was.

The delusion is further illustrated by the fact that analysts such as this one, who argued before the election that the EFF would not achieve Cope's share of the vote, were insulted and abused, accused of being blinded by our prejudices.

Now the outcome we predicted is said to be proof of the EFF's popular appeal. While Lekota is rightly derided by the media for predicting his party would receive 20 percent when it achieved less than one, Malema is hailed despite predicting the EFF would win over 50 percent.

Of the votes it did receive, 40 percent came from relatively affluent Gauteng. It also may be no coincidence that EFF's vote is about half the 10 percent or so who use social media. It remains likely that EFF voters were, in the main, not the poor and marginalised, but the middle class and the connected.

But why then has it been portrayed as so popular a force?

First, it inspires some of the middle class's deepest fears. Central to the South African story is a myth once embraced almost exclusively by whites, but which has become embedded in the world view of much of the middle class.

It sees the poor as irrational barbarians, prey to the promises of any demagogue. And so any populist who seems to be urging the black poor to rise up and seize the wealth of the affluent is assumed to enjoy mass support.

This explains why Winnie MadikizelaMandela was assumed to be a leader of the poor and why Malema and the EFF have taken over this mantle.

This fantasy ignores overwhelming evidence that living in poverty is no bar to rational thought and that poor people are perfectly capable of knowing who represents their interests and who does not.

Since most know that the EFF leadership is far more familiar with the world of the rising middle class than that which they endure, they have no reason to support it. Since many poor people in Malema's home province, Limpopo, also associate him with using public resources in ways which do not assist the poor, it is no surprise that one in 10 voters there rejected the EFE

The second reason is wishful thinking among those who are so eager for social and economic change that they latch on to implausible signs that it is happening.

The EFF may sound radical, but its chief message is racial nationalism, not social justice. It is led not by a leader elected by its members, but by an anointed commander-in-chief. It reacts to most issues with threats that it will use not political action, but force.

Those on the left who have embraced the EFF have disregarded the difference between a movement for social equality and a nationalist populism with strong militarist undertones. A middle-class movement concerned, not at inequality but at the race of those who benefit from it, becomes a radical justice movement with deep roots among the poor.

The EFF is not the people's movement that will challenge the post-1994 era's skewed distribution of power and privilege: that is yet to emerge. It is, rather, a trigger to the mainstream prejudices and left-wing delusions, which obstruct an effective challenge to social injustices.

· Friedman is the director of the Centre for the Study of Democracy at Rhodes University and the University of Johannesburg

This article first appeared on the website of the SA Civil Society Information Service, www.sacsis.org.za and is licensed under a Creative Commons Licence.

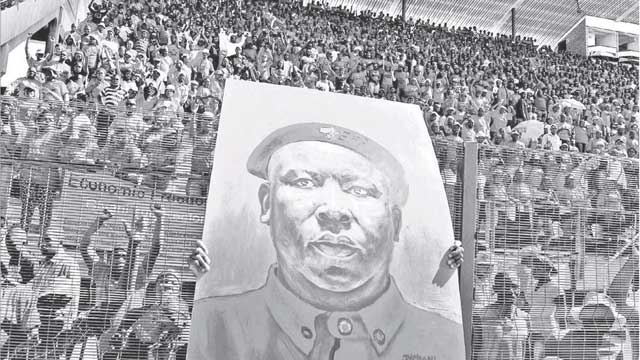

POSTER BOY: That this history-changing movement turns out to enjoy the support of only one in 16 voters, if we take into account how many people register, one in 29 voting-age citizens, shows how great a delusion the notion of EFF as a history-changing mass movement is, says the writer.