They are like so many cages, so many small theatres, in which each actor is alone, perfectly individualized and constantly visible. The panoptic mechanism arranges spatial unities that make it possible to see constantly and to recognize immediately . . . visibility is a trap

(Foucault 2008 [1975]: 5).

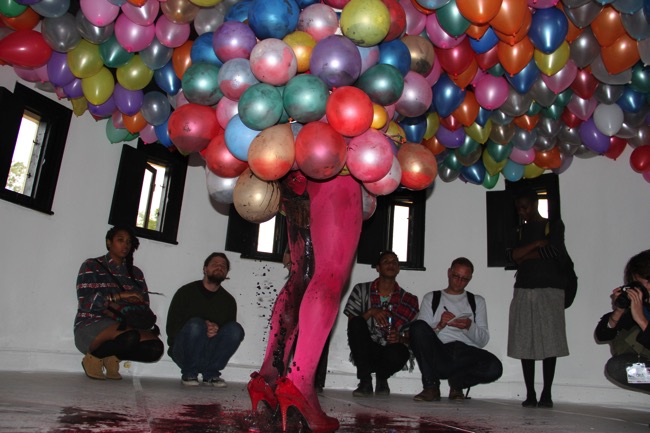

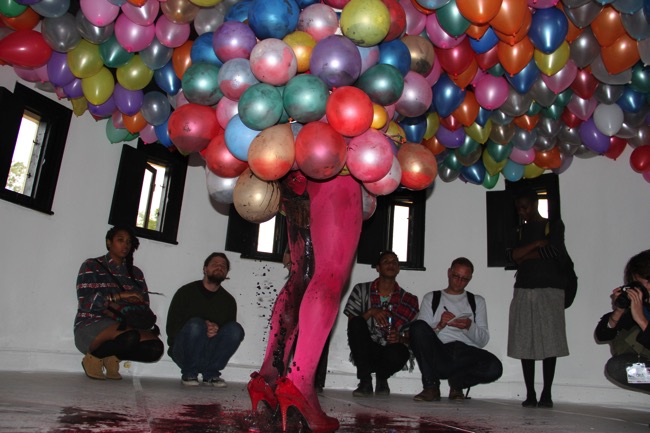

The second performance that Athi-Patra Ruga produced for the Making Way exhibition took place in the upstairs room of the guard’s watchtower of the Provost Prison, which draws from the architectural principles of the panopticon. In this work, the Future White Woman of Azania stood in the middle of the guard’s tower, her balloon costume filling the entire ceiling, hindering the movement of the audience. While some viewers looked out of the narrow windows that line up with sightlines leading to prison cells, other viewers could watch a livestream of the performance inside one of the prison cells, reversing the direction of the panopticon gaze. Recorded sounds of spanking played in the background, confounding clear-cut notions of prisoner and guard, of who is watching whom, who is punishing whom, and who might be regarded as trapped or free. The Future White Woman of Azania, who stood in the position of the prison guard, slowly leaked as she punctured paint-filled balloons, alluding to the vulnerability of positions of power.

Photos and text: Ruth Simbao (please do not use without copyright permission)

THE TRAP OF VISIBILITY AND THE DISCURSIVITY OF SEEING

Below is an extract from the Making Way catalogue that draws together various works in the exhibition that overturn straightforward ideas about seeing.

“A number of the venues used in the Making Way exhibition in Grahamstown are associated with particular types of seeing and are designed in relation to strategic visibility. Fort Selwyn, for example, is placed on top of Gunfire Hill with a view of the city below. The cannons within the fort wall suggest that the position of the fort was constructed around the visibility of the ‘enemy’. The Provost Prison is based on a panopticon design, and consists of a double storey tower with narrow windows that open onto sightlines in the prison courtyard that lead directly to each cell. As such, a military guard placed in the central tower “sees everything without ever being seen” (Foucault 2008 [1975]: 6). As Foucault (2008 [1975]: 5) writes in Discipline and Punishment:

Each individual, in his place, is securely confined to a cell from which he is seen from the front by the supervisor; but the side walls prevent him from coming into contact with his companions. He is seen, but he does not see; he is the object of information, never a subject of communication. The arrangement of his room, opposite the central tower, imposes on him an axial visibility; but the divisions of the ring, those separated cells, imply a lateral invisibility.

Upstairs in the guard’s tower of the Provost Prison, Wu Junyong’s animation videos Flowers of Chaos, (2009) and Cloud’s Nightmare (2010) accentuate and play with the notion of ‘seeing without being seen’ as silhouetted figures are viewed through the circles of binoculars. Animated hands pull on strings and manipulate puppets in an absurd “theatre of revelry” (Chen Xiaoyun 2011: 5) that explores issues of power, greed, monotony and futility. As Gao Shiming (2011: 3) writes, “For Wu Junyong, the world is a circus, life is performance, diverse yet monotonous”.

While Wu’s work reveals “voyeuristic observations toward the society, a malevolent yet self-entertaining voyeurism” (Gao 2011: 3), there are moments of reversal as close-up eyes stare back into the binoculars and a figure peering through binoculars is simultaneously viewed through another pair of binoculars, creating layers of seeing, rather than straightforward lines of sight. No longer is each individual securely in his place, for imaginary events break through the categories of the rational and the mundane: human beings fly, chairs and horse heads walk on stilts, men wear horsetails, and a figure rides on the back of a chicken. “We are not clear”, says Chen (2011: 5), “whether there is a reality only known by Wu Junyong behind this virtuality, or to Wu Junyong, the reality is just a theatre, a scene of changing props, a group of manipulated clowns, a mysterious formula of the world behind the curtain . . . clueless plots, carnival-like monkey business mixed with loneliness, and mechanical-like mischief”. Placed inside the Provost Prison, these works open up the “house of certainty” (Foucault 2008 [1975]: 7) and unleash a fiercely imaginative way of seeing the world in which “nothing has to be defined, [and] nothing has to be opposed in the same manner” (Chen 2011: 5). For Wu, “an alchemist who relies on his boundless imagination and persistence, the outside world is only a puppet of his innermost self” (Chen 2011: 5). The panopticon, as such, becomes a house of uncertainty, in which it is unclear what is being seen, who is looking at whom, and what sights or visions can be trusted.

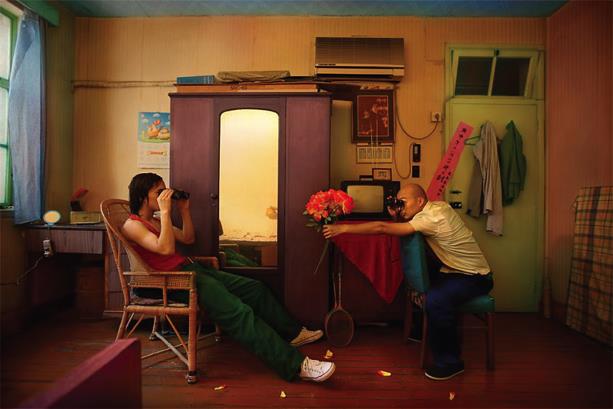

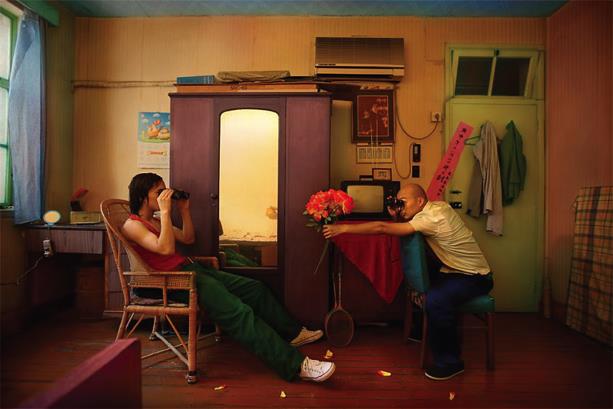

Maleonn similarly plays with the failure of straightforward seeing. While in Wu’s Flowers of Chaos peripheral vision that falls outside of the rings of the binoculars is blank, in Maleonn’s Amber #7 the viewer of the work sees what the figures peering through binoculars are unable to see. Two young men sit in a small apartment, a short distance apart, and peer at each other through binoculars as if a literal distance needs to be overcome. Perhaps the binoculars—the tools of seeing—are a crutch for dealing with a metaphoric or emotional distance, a distance that the viewer of the artwork cannot see. While one man casually lounges in a chair, as if he is unaware of being watched, the other man eagerly leans forward to offer him some flowers. Both protect the nakedness of their own eyes.

In Déjà vu #2, a goggled woman stands poised with a stick for the blind, about to make her way with the guidance of a rabbit. However, instead of guiding her, the little white rabbit, often associated in China with good luck, nibbles on a carrot while the woman patiently waits. It is not clear whether or not the woman is blind, or if the goggles are transparent or opaque, but apparent blindness becomes a metaphor for the uncertainty of clear-cut vision. The title Déjà vu further emphasises slippage, for while you see or feel something in a flash that you think you have seen or felt before, you are not sure, for your imagination plays with your mind, confusing sight, memory and an entire universe of the potentially unreal. Seeing makes way for a discursive window to the world” (Simbao 2012).

To view the full exhibition catalogue click here

Photos: (top) sightlines of the Provost Prison in Grahamstown viewed from the guard tower (second from top) Athi-Patra Ruga viewing the camera obscura tower in Performance Obscura (middle), Wu Junyong, Flowers of Chaos, courtesy of the artist and F2 Gallery, Beijing, (second from bottom) Maleonn, Amber #7, courtesy of the artist (bottom) Maleonn, Déjà vu #2, courtesy of the artist

Text: Ruth Simbao

Funding was received from the National Arts Festival